After my fiancée, Zoe, moved out of our two-bedroom condo, I became obsessed with spelunking documentaries.

It started as a sort of hysterical inside joke, this obsession, if I can share an inside joke with myself. Unable to sleep, one night, for reasons I’d rather not dive into—reasons that should be clear to any man who’s ever been jilted not because of something he did, but because of the kind of person he is (the day she moved out, Zoe branded me “irredeemably frigid”)—I found myself laughing at a documentary called Extreme Cave Divers.

Extreme Cave Divers was about a team of underwater archaeologists, or, as the English narrator christened them, “astronauts of an inner space.” The archaeologists were each armed with graduate degrees and flippers, and they dove thousands of feet deep into underwater caves off the coast of the Bahamas, in search of bones, soil, and other subaqueous artefacts of antiquity. The archaeologists were all burly men over forty, possibly fifty. And I found it quite funny, on that otherwise quite unfunny night, to see them risk death to explore very deep, very womb-like holes.

“You emerge from the cave,” said one especially burly spelunker in the documentary’s final shot, “and it’s like you’re reborn.”

Reborn. Ha! What a choice of words. I was hooked.

That same sleepless night, I went on to watch Under the Antarctic, then Deep Sea Exploration, and then the sun was splintering through my blinds and how did I spend the rest of my weekend? By watching more documentaries.

I called in sick to work on Monday, then again on Tuesday; by Wednesday, I hadn’t left my condo in five days. I ordered all my meals from a vegetarian restaurant, near Trinity Bellwoods, apparently frequented by Toronto Blue Jays players. The giggly receptionist and I grew so friendly, over the phone, that we started addressing each other by our porn star names. My porn star name, she informed me, comprised the name of my first pet plus the name of the street where I grew up. I was Humphrey Dovercourt. She was Ruby Russell.

I dialled Ruby Russell to order squash tacos and a double shot of wheat grass—but someone, it turned out, was already calling me.

It was my Creative Director, Steven—not Steve (I made that mistake once, and never again). I work as a Junior Copywriter for a pretty prestigious advertising agency, based in Liberty Village, and that week my main assignment was to draft potential brand names for an outer-space-themed tube of organic baby food. (“Baby Food Tube?”) Steven asked me if I’d come down with a throat infection. He said throat infections were spreading through the office “like the Black Death.” I told him I did have a throat infection, plus an earache. I said it was tough for me to hear him and also painful for me to speak.

“The good thing about a throat infection,” said Steven, “is that it’s not a mind infection.”

I mustered a cough. “Pardon me?”

“YOU CAN STILL BRAINSTORM NEW SLOGANS FOR THE MUSH TUBES.”

“Thanks for checking up on me, Steven,” I said.

Then I collapsed on my bedroom floor and ogled the pale spot on the wall where Zoe’s pink Diane Arbus print once hung.

Zoe adores pink. I’ve never minded pink. One night, when times were still good, she said to me, post-coital, “Most men say they dislike pink, but you’re not like most men.” Then she kissed the back of my neck—I was little spoon—which always put me to sleep.

Who would sedate me with soft kisses now?

I stood up. I threw out the take-out boxes that had piled up in my condo like little, grease-stained bodies killed by the Black Death. No more dawdling. I was hurting, sure. But as I jammed the boxes down the garbage chute, I realized I wasn’t hurting as deeply as I should have been, and therein lay the problem: that I didn’t hurt as deeply as I should have proved Zoe right: I was “irredeemably frigid.” But did I want her to be right? No. I wanted her to be wrong. But for her to be wrong, I needed to hurt more. And I didn’t want to hurt more—I wanted to hurt less. I needed to hurt less. I needed to hurt less so that I could do important things, like sweep my bedroom floor, draft titles for the cosmic baby mush tube (“Big Bang Baby”?), and find a new roommate.

Because I needed a new roommate, pronto. I couldn’t afford the rent for my two-bedroom condo on my own. Together, Zoe and I had been financially stable. She works for a law firm that specializes in intellectual property, so between us, we’d been doing all right, financially speaking. Our condo, before it became just my condo, was uncluttered, spacious, Zen. Boston Ferns hung from wooden hooks affixed to carbon T-bars. The fridge filtered tap water into a substance that tasted like purity liquefied. Our condo was a clean, well-lighted place. Any friend would’ve been damn lucky to move in with me. Yet my problem, or another one of my problems—and this is something that struck me while watching Spelunking in the Deep at sunrise—was that I didn’t know who among my friends I could ask to be my roommate, since I didn’t really have friends anymore.

Don’t get me wrong—I used to have friends, during university in Montreal, before I moved to Toronto for grad school and met a law student named Zoe. But the years went by. Distance accumulated. Friends moved to different cities. For a while, none of us could afford to visit each other, and by the time some of us could, it had been so long that it felt kind of awkward for me to visit them, even presumptuous—presumptuous of me to assume my friends wanted me to visit. Plus, I am a socially anxious person. Socially, and also when alone. How could I not be anxious? The Black Death killed at least seventy-five million people. Per attempt, cave diving is the riskiest sport on Earth. Also, I had a work deadline looming, and idea-wise, I was tapped. What did babies even like about outer space? Did babies even know what outer space was?

So I opened my laptop to search out a short film I’d seen once in New York about the Big Bang, but quickly found myself pulled into the black hole that is the internet—all in the hope of better marketing mush tubes. To my surprise, I learned that, before the universe started expanding forever, it actually contracted—forever. It’s confusing. Let me try to explain. Until fourteen billion years ago, said some esteemed physicists, the universe was shrinking, and this shrinking took place before the Big Bang, yet also, in a certain sense, after the Big Bang. How? Because time moves in two directions. The universe is like a slinky, said physicists, one that slinks down to the floor, reaches maximum compression on impact, and then bounces back to its larger dimensions. The behaviour of the contracting universe more or less mirrors the behaviour of the expanding universe. And this means that anyone who lived in the contracting, mirror universe—where, plausibly, there was a mirror version of me—would have viewed the Big Bang as belonging to the past, just as we do. Thus, our very sense of time, said physicists, has everything to do with the Big Bang. The reason we can see the past but not the future is the Big Bang. The reason I could not foresee Zoe leaving me is the Big Bang.

Although, come to think of it, that’s not entirely true, because I did foresee it. This happened a month before Zoe jilted, during a miserable jaunt through the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, which she had loved to explore as a kid. We’d gotten ourselves into a little fight that morning, and by “little” I mean “catastrophic.” After a forebodingly unvocal breakfast, rich in riboflavin, Zoe said to my reflection in our Airbnb bathroom mirror, “You act like you don’t love me.”

“But I do love you,” I protested, mouth foaming with toothpaste. (“Tube Space Baby Paste”?)

“Show, don’t tell.”

So that day at the museum, our relationship was on the rocks, and this phrase, “on the rocks,” looped in my mind, like the chorus to some jarring jingle: “On the rocks/On the rocks/Zoe and I are on the rocks!” I found myself craving whiskey. Zoe likes hers on the rocks.

We entered the darkness of an oval-shaped movie theater, where an animated film aired on a colossal screen below our feet. The narrator of the film was Liam Neeson, an actor, and his intention was to explain the Big Bang in four minutes. The film made me vertiginous, and I did not understand it. I don’t think Zoe understood it either, but she was too unhappy to show me any signs of vulnerability, so she acted as though she did. Afterward we emerged onto a spiralling ramp that charted, via text and photographs and primeval rocks, the history of the universe. With each step, we traversed billions of years.

“Time flies when you’re having fun,” I joked.

Zoe didn’t laugh.

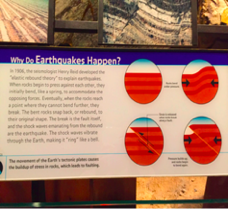

I descended the time ramp behind her, learning about dark matter, light speed, novae. By the time we reached the bottom, I felt both miniscule and enormous. “Where to next?” I asked, but the question turned out to be rhetorical, since we had no choice but to enter a hall called “Nature’s Fury: the Science of Natural Disasters.” Zoe went off alone, so I did likewise. Alone, I jumped on a scale that measured my magnitude in Richters. Alone, I learned how mountains rise. And then I experienced a forecast of my future. It was triggered by a plaque, titled “Why Do Earthquakes Happen?” which I took a photo of:

[In 1906, the seismologist Henry Reid developed the “elastic rebound theory” to explain earthquakes. When rocks begin to press against each other, they initially bend, like a spring, to accommodate the opposing forces. Eventually, when the rocks reach a point where they cannot bend further, they break. The bent rocks snap back, or rebound, to their original shape. The break is the fault itself, and the shock waves emanating from the rebound are the earthquake. The shock waves vibrate through the Earth, making it “ring” like a bell.]

This plaque, I felt, trembling with a sudden chill, knew my future, our future. (“Future Baby!”) It forecasted what was happening to Zoe and me: we were pressing against each other, like two rocks bending to their limits, and soon we’d snap back to our original shapes, soon our world would “ring” like a bell.

Which leads me now to dive finally into the conundrum that animated my insomnia after Zoe left me, the conundrum that kept me awake each manic night as I spelunked into the dark caves of my memory—me, an “astronaut of an inner space”: Why in that moment with the plaque, when I saw the future—our future—did I not behave differently? Why, when Zoe shuffled over to me and squeezed my trembling hand and asked if I was okay, did I not answer truthfully? Why did I pass off my pain with some shallow joke?

Lying awake in bed those manic nights, watching documentaries about spelunking, I could not stop myself from fantasizing about my mirror self, the self that might have lived in the contracting, mirror universe. I could not stop picturing him, while all but genuflecting before that prophetic plaque about earthquakes, waiting for mirror Zoe to squeeze his hand, as she’d squeezed mine, and ask, “Are you okay?” And I could not help but hear him, unlike me, admitting, “No.”

Gavin Tomson's short stories have appeared in Joyland and Dalhousie Review. His essays and reviews have appeared in Maisonneuve and LARB Quarterly Journal. He's the winner of Dalhousie Review's inaugural short story contest and his fiction has been shortlisted for Pen Canada's New Voices Award. An earlier version of "On the Rocks" was a Finalist of The Writers' Union of Canada's 23rd Annual short Prose Competition. He lives in Toronto.

Gavin Tomson's short stories have appeared in Joyland and Dalhousie Review. His essays and reviews have appeared in Maisonneuve and LARB Quarterly Journal. He's the winner of Dalhousie Review's inaugural short story contest and his fiction has been shortlisted for Pen Canada's New Voices Award. An earlier version of "On the Rocks" was a Finalist of The Writers' Union of Canada's 23rd Annual short Prose Competition. He lives in Toronto.