We used to write tally marks on our grandmother’s feet—blue or black pen on her tight, dry, varicose skin just below her ankles. She couldn’t see the marks. She didn’t know about them.

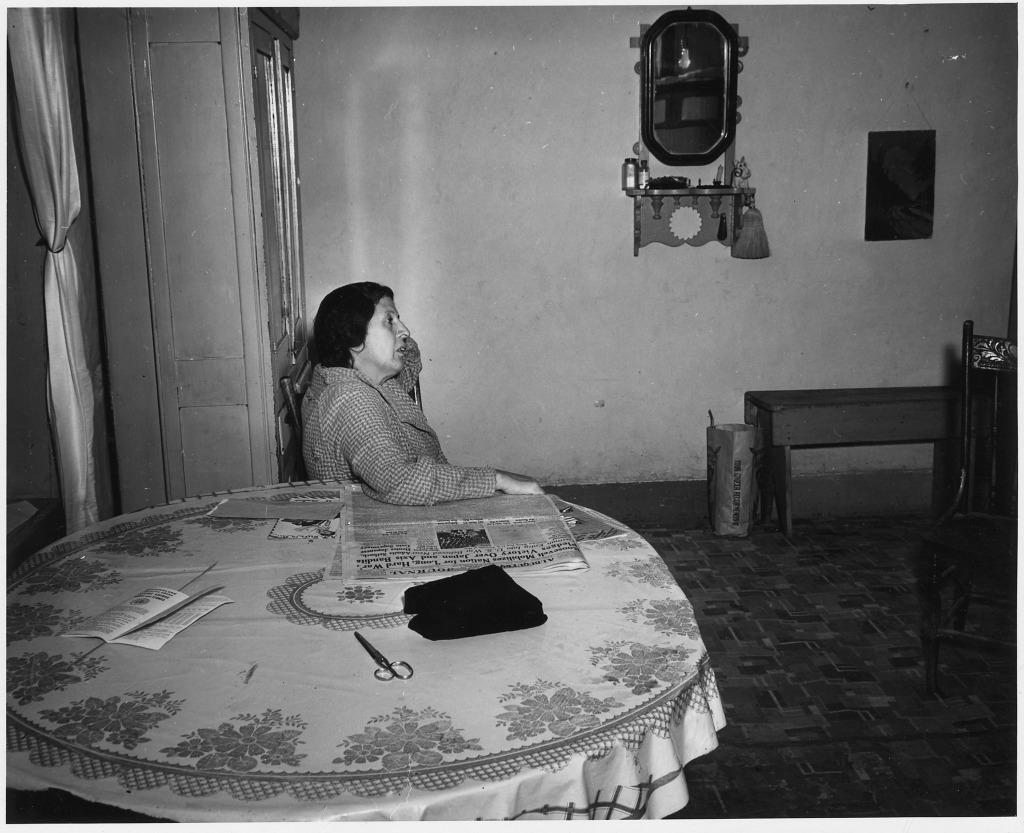

When her husband (our grandfather) was alive, she patrolled the household. When he died she put down the soup that she had just prepared for him, closed his mouth and his eyes, raised a blanket over his face and sat down. She outlived him for thirty years and she sat for that period—sleeping in her chair, eating in her chair. We tended to her.

She sat with her head slightly tilted to the left and a softly grimacing face, always looking straight ahead. She spoke rarely. Occasionally the local doctor would come to the house to help us. He would talk to her and talk to us and occasionally he would use long words. ‘Some kind of dissociative state’, we repeated to each other after the doctor had gone.

She wasn’t always seated. That would have been quite difficult for us to manage. She would occasionally stand up so we could wash her skin or so she could shuffle to the toilet. If she did speak it was while she was walking. As the years passed she started to sense something about her feet and she would have a certain way of describing it. It’s like walking on stumps, walking in someone else’s feet, walking in fuzz, walking in a dream. She used the dream description the most often.

The doctor called this gradual worsening ‘neuropathy’—which we later found two ways of pronouncing—it meant her nerve endings were dying.

The problem gradually spread and was very noticeable when it got into her hands—brushing her teeth and eating with a knife and fork became difficult. We helped her with these.

Credit: Wiki Commons

Thirty years is a long time. For us, the grandchildren, it has been the majority of our lives. Over that period it’s difficult to describe our changing relationship with each other.

What could we say?

Perhaps, over the years we had arguments and we forgot arguments; we fought and we forgot fighting; we used new impolite combinations of words and we forgot old combinations; ‘cocksucker’ was popular for a while and then we forgot it. Uncles and aunts came and went and we forgot some of them too. Our grandmother didn’t acknowledge anything except the lack of feeling in her feet and hands as she walked to and from the toilet, with no help.

Managing winters was never part of our routine before our grandfather died. Since then they have been getting longer and longer, up to five months or so. On the very cold days our eyes cried and our breath froze in any facial hair that we might have had that year and it gave us patchy white beards or sideburns. The dry winter air that came with it started cracking our skin, making it itch and sometimes making our knuckles bleed. We had to start moisturizing our own skin, something we had never done before. Over the summer our skin healed but never regained its youthful stretchiness.

Snow storms became more frequent. We listened to the radio forecasts and could never imagine that fifty plus centimetres could drop in a twenty-four hour period. But it did, so large and light, that it would seem to take forever for the flakes to hit the ground. The wood in the rafters of the roof soon moaned under the weight of the snow.

We starting keeping our snow shovels in the house, beside our gloves and winter shoes, as it was likely that we’d have to dig our way out. We’d open the front door tentatively; one person holding the door, another holding a shovel. We shovelled some of the snow, careful so that the rest didn’t collapse into the hallway, and walked it through to the bath for it to melt. Once our whole bodies could take a single step out of the house we started to throw the snow into a pile outside, away from the doorstep, and then we made quicker progress along the front path and eventually to the road.

We threw shovelfuls of snow, out of the trenches we were now cutting, that sometimes the wind whipped back into our faces. And so we shouted at each other not to throw snow into the wind. Our necks and wrists got sweaty and the beads of salt burned across our dry skin. We removed our toques and our hair steamed thickly like it was smoking. It was usually during these moments that we argued about our grandmother’s involvement with the weather.

The roof was always our primary concern. We’d heard about one collapsing on the other side of town because of the weight of snow. We kept a dug channel around the house so we could open the step ladder and reach up, encouraging the snow to slide off with our shovels. We also knocked off the snow that overhung the side of the house impossibly, like the corner of an untucked white sheet.

There were multiple record breaking snowstorms and it was cold enough that the snow barely melted. As we cleared the front path to the road and the path around the house, we made a pile of snow that circled the house like the outer walls of a castle. During the shorter days of winter this pile would block direct sunlight through the windows. When we were young, we would climb up and sit on the ramparts and survey our house: it was separate from the world.

Our defences were strong enough that they wouldn’t fully melt away until the intense heat of mid-summer.

Between caring for our grandmother and digging the house out of the snow we started playing cards. We played at the kitchen table. It had enough seats and a laminated surface good for dealing. We left our grandmother in the lounge or wherever she thought she was. I don’t think anyone asked her if she wanted to play. She couldn’t have held the cards, they would get lost in her dreamy hands.

We’d learn games and teach them to each other and then beat each other. As we learnt new ones, we’d forget the old ones. We learnt bridge and forgot whist; we forgot Napoleon and learnt Slippery Sam and Blind Hookey. We also learnt about variations of games, how to best play them with different numbers of players, and the appropriate strategies for each. We got very quick at dealing, shuffling, fanning and ordering our cards.

If one card in a pack had a corner that was bent, or if the cards were starting to warp through shuffling, of if one was slightly torn, we got rid of the deck. We’d strip the cellophane wrapping off of a new pack, slide the cards out, remove the jokers and shuffle the deck in a smooth continuous motion so there was never much of a pause between hands. We liked the cards shuffled well and dealt smoothly.

Someone—we don’t know after how many years—put a tally mark on the felt underside of a round drinks coaster. A little blue mark, a reference to a card game won. We can’t remember the game now. The tally marks on the coaster multiplied, more rapidly perhaps through the long winters, until eventually all available space was occupied, the tally marks curving slightly as they got packed at the edge.

After that we started marking the reverse side of the kitchen clock, underneath candle stick holders, table lamps—our pens preferred anything wooden or painted. Plastic and metal surfaces were difficult but permanent marker worked on them.

As we forgot more games and learnt more games we marked the reverse face of everything. We tallied the whole house—ashtrays, china plates, and microwaves. Our pens ran out and we bought more pens.

The insides of cupboard doors, the back of opaque curtains, under rugs and on the inside of drawers and cupboards, and the back of picture frames.

To see them all, to fill the visible house, to fill the natural sightlines—and more importantly, to see who was winning—you’d have to turn everything round or upside down, essentially turning the house inside out.

It’s hard to imagine what the pressure of blood in our bodies is? We can’t picture it or feel it. There’s no reference. We are just told by the doctor when it’s not the right number.

Could we have compared it to the pressure of the snow on the roof? We could work that out from the weight of a shovel of snow perhaps.

There was one natural effect for visualizing the pressure of blood that we hadn’t anticipated. It coincided with our grandmother standing up at a moment we hadn’t anticipated either.

She was in the lounge, now standing in front of her chair. We were at the kitchen table playing a two or a four player game, we can’t remember—bridge or cribbage, perhaps. We heard her, not shouting but loudly shooing something. We needed nothing more than a quick glance at each other before we ran to the lounge, filtering into single file.

We turned on the light and we saw our grandmother trying to bend forward. She was flapping her hands, shooing something lower down around her feet like it was an animal.

We looked at her feet.

Our grandmother was leaking.

Not a gentle trickle but a comical, narrow, single pressurized-stream was arcing between her legs from one ankle to her other foot.

As she moved her legs to fend off the animal, the stream also went onto the floor. We were watching a rich red Jackson Pollack drip painting in progress—hooks and hairpins and curves and switchbacks. One of her varicose bumps had split.

We put pressure on the cut, stood her upright, holding her hands to stop them from waving, and sat her down and raised her legs.

She couldn’t feel our hands on her feet as we stemmed the blood flow, which stopped surprisingly quickly. She couldn’t understand where the animal had gone. As we were salting the bloodied carpet we told her that we’d opened the back door to let it run away.

We couldn’t completely remove the blood stains so all we could do was cover them with a small rug—well, not that small, it would go on to contain thousands of tally marks on its underside.

The doctor gave our grandmother a tight synthetic sock to wear that came up to just below her knee, to put the blood pressure somewhere else in her body rather than her left ankle. Immediately we had a new image for blood pressure. The weight of snow comparison didn’t work. It was like a sachet of ketchup. That was a better image. The sock was squeezing blood around like finger tips on the ketchup sachet. We hoped that she wouldn’t burst anywhere else.

Her dead nerves didn’t tell her if she had the sock on or not. We kept adjusting it, to comfort her from a restriction she couldn’t express and to make sure the ketchup was getting to her cold feet.

During one of the sock adjustments, on one of the days, a tally mark was drawn just below her ankle, we think the first was in blue ink.

We knew who drew the mark, but it was never mentioned. It was never mentioned as we stopped talking to each other.

This breech of taste drove us to prepare our own meals and dig the house out of the snow individually. Our grandmother also became remarkably clean as we washed her, regardless of routine or bowel or bladder accident.

We walked around the kitchen silently, preparing and cooking our own food and only doing our own washing up. If two people wanted to use the same pot, one would wait silently, cooking the food with their eyes. We shared some of what we prepared with our grandmother and each of us hoped she liked our food better. She gave no real indication of whose she preferred, nothing clear-cut like the result of a game of cards.

Through the silence we started playing even more cards. We’d sit down and someone would start dealing and from the number of cards we received we knew what we were playing and we continued. The dealer always rotated clock-wise, and if the new dealer wanted a different game, they dealt the appropriate amount of cards for that game.

The snow still needed clearing but we would sit at the kitchen table, with cards in our hands, looking at each other. The roof would creek and one person would eventually lay down their cards and go to the front door with a shovel. The rest of us put down our cards carefully so no one could see them, picking up a shovel each and going outside and working around each other. We lacked coordination, accidentally throwing shovel loads of snow so the wind would blow it and cover another, and not helping someone when they were buried by snow falling from the roof. We’d watch them dig their way out; they were like animals coming out of hibernation.

Eventually, through the frustrations of card games and snow removal, we started to talk again. We decided what game we wanted to play first, and then next, and so on. Between hands we started to talk about our grandmother. We talked about what we had been thinking since her foot had been marked, that people were not happy, that they had thought of leaving for a while—to take care of themselves perhaps.

We also verbally acknowledged the reappearance of uncles and aunts who we didn’t recognize initially as it had been so long since we’d seen them. We think divorce brought them home. They merged into our card games and our re-established snow shovelling teamwork.

And through this period more marks appeared on our grandmother’s foot.

It’s true that she couldn’t feel them being drawn because of the dead nerves—by this point she was dreaming up to her knees and walking had become quite perilous and so the doctor gave her a Zimmer frame to push in front of herself.

It’s true that she couldn’t see them. With her socks on, of course she couldn’t. But even when they were off she would never look down, she didn’t have the inclination to turn her natural sightline inside out to see her feet in detail.

On top of all of that, she wasn’t really looking. Perhaps she was concentrating on seeing how well we got on digging out the house.

Our grandmother had by now completed a breath thousands or millions of times. It was getting to a point of her frailty where the completion wasn’t inevitable. It was as if she was searching for a memory to trigger the next quenching inhalation—a memory of us as little children competing for attention, to be the last bathed and put to bed, or our grandfather’s return from work each day in time for the evening meal.

The doctor’s visits became more frequent. He came with his own snow shovel in case he had to dig out his car from the accumulation while he was here. His face became more serious also, not just from his frustrations of the deepening winters, and he talked more quietly. We often asked him to stay for a game of cards, but he always politely declined, picked up his shovel and left.

We think he called this laboured breathing of our grandmothers ‘agonal’—it was a sign of late old age. We repeated this word to each other later, ‘agonal’, ‘agonal’. It was curiously close to the word agony.

The doctor said there would be another stage, where our grandmother would start to make an involuntary noise called a ‘death rattle.’

At the kitchen table after he had gone, as someone shuffled between hands of cribbage, we would imagine where the sound came from. We sat bubbling and gargling saliva in our throats trying to find the right rattle. Some of us coughed from our efforts and had to drink water to sooth the tickling.

It was after weeks of agonal breathing that she started to make strange sounds. We stopped playing cards and we stopped making our imitations of the ‘death rattle.’ We sat around her, holding her hands. Her breaths were preceded or followed by clicks and rushes of air which were so tired that it became difficult to imagine the next one.

Our grandmother stopped breathing. It’s difficult to say when, as we had become lost within the metronome of her breath, after which then we got lost within the metronome of her silence. We might have sat around her for hours before we called the ambulance to come and confirm her death and to take her away.

We heard the ambulance arrive. It was only then that we noticed that the house had been buried in snow again. We stood at the front door as we watched the paramedics try to walk and balance their way through the waist high snow, dragging the stretcher with them. The depth of the snow made it difficult for them to raise their legs high enough to make the next step and they kept putting their hands on the snow walls either side of them to avoid falling over.

After watching them for some minutes we started to dig our way out of the house, filling the bath with snow, running the hot water tap to melt it quickly. As we did this the paramedics turned back to collect their shovels and then started digging from the other direction.

We must have shovelled for an hour, unzipping our coats and removing our toques to dry off our sweaty foreheads. Some of us stirred the snow in the hot water to help it melt quicker. When we were a few meters from each other the paramedics made the large step over the remaining snow, came into the house, took their winter boots off and propped their shovels against the door.

We were gathered as the paramedics put her onto a stretcher. They took off her socks and we all saw the tally marks, we all got closer, each trying to total the scores in our minds. They covered her with a sheet before we could finish counting. As the paramedics put on their winter shoes we were trying to pinch a corner of the sheet so we could see all of the marks. As the paramedics left the house, they re-covered her feet again and started sliding the stretcher through the snow. We put our winter boots on quickly and we followed them through the snow-walled channel that was deeper than us. The snow gathered in the wheels and they stopped turning so they jerked and slid the stretcher and her feet poked out again.

We looked at each other and then jostled, pushing each other into the snow banks so we could get closer and continue counting the marks on her toes, between her toes up to the nails (which we trimmed frequently), under the ball and arch of the foot, around the heel, and we started to count up the leg. The paramedics lifted the stretcher over the remaining snow on the path and we pulled each other back by the leg or arms.

They opened the ambulance door and we again tried to pinch a corner of the sheet to uncover the rest of her leg. We thought we could compare counts after she had been taken away. Our hands stung from the cold. The paramedics lifted the stretcher higher and pushed it into the ambulance, folding its legs as it went in. They asked us to step away from the door so they could close it. Instead we went up onto tiptoes, trying to get higher than each other, almost finishing the count of the tally marks to see who had won after the thirty years of cards. They said they know it’s difficult but she lived a long life and she died peacefully of old age. We stepped back and the paramedics shut the doors and some snow fell off the roof. We stepped away to avoid it.

We stood shoulder to shoulder, our relative heights now settled in adulthood. We never did finish counting the tally marks.