carte blanche‘s Chalsley Taylor sat down with Morissette to discuss writing, accessibility, book tours, and mental health. This interview was conducted in person in October 2014, in Montreal. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The last time your work appeared in carte blanche you were writing poetry generally; is that true? Or do you move between genres?

The piece for carte blanche was early 2011, so that’s a while ago. I was trying things out and trying to get published in different places. carte blanche was one of the first places that actually paid me for a piece of writing, so that was validating. When I went into creative writing, I wanted to do fiction. I was interested in working on short stories and eventually working my way up to novels. When I first started, I would write these third person stories that weren’t necessarily very close to me; I would start with a fictional premise and take it from there, but I always found a way to include certain details, like for the main character there would be an anecdote or something that was more or less taken from my life, and those were the parts that I felt were the strongest.

I went to poetry as almost like a side note, because I wanted to get readings and it was easier to send someone a one-page poem than a ten-page story. So I ended up getting readings that way, but I never intended to be a poet. My poems weren’t very poetic because I didn’t see language as beautiful. I saw language as pragmatic, so my poems looked like emails gone wrong or something. I kind of liked that I didn’t have a fixed ideal of what I wanted to accomplish with poetry. With poems, I would use the first person “I” a lot more, and my work was much more intimate as a result, so when I went back to fiction, all of a sudden I felt like I was able to work much closer to me, so it was an interesting detour for that. I definitely learned from poetry, but I think I saw it as developing a certain set of tools that I could use in another context. I don’t think I ever really wanted to pursue poetry full time.

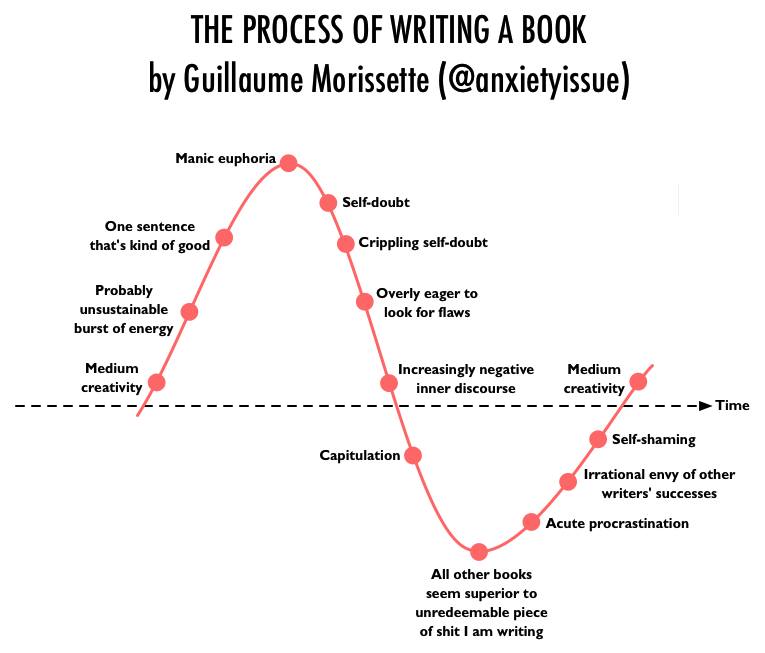

Where do you situate your charts in relation to your other writing? Because while I consider them creative writing I wouldn’t try to squish them into any existing literary genre.

To me, they definitely have a literary component. The thing is that online, it’s helpful for me to have a visual identity as well as a written identity. The charts are images. I can share them on Tumblr and stuff, and you don’t consume them the same way you would consume text. There’s this Tumblr called “I Love Charts,” you can get a lot of views just from them reblogging your work, so it’s good exposure. It wouldn’t work if I was to send them a poem. They would just be like, “What the fuck is this?”

When I say visual identity, it can mean a number of things. The chart thing is kind of part of that, but there’s also just the way I present myself on social media, like “oh I’ll choose this profile pic”—

Yeah, I think you’ve got a real handle on that visual identity thing.

You know what I mean, though? It’s kind of like, the web is a really good medium for text, but it’s a good medium for images as well, and it’s much easier to understand an image than to understand a piece of text. You can understand an image almost instantly, and that’s kind of what I like about the chart thing. You look at it and in a single moment, you understand, “Ok, this is some chart thing, it’s meant to be funny.” So, whether you want to examine it in full or not, you can make your decision instantly. With a poem, it would be like, “What is this really about, do I get this? I am afraid.”

Do you think you sacrifice anything in creating a chart? Because my impression of the charts is that they’re very good at revealing a troubled interiority, they’re very expressive and confessional. So do you see any drawbacks?

I think I see it as entry-level me, something that has a very low barrier of entry because it’s free, and easy to access, and easy to understand, so it can draw people to my Twitter account or my whatever, and hopefully the goal is that you have things that require different levels of commitment. The chart thing is very surface-level, then you can have an essay that I’ve done that’s still free, but you need to read it, so that takes a little longer. Then you have my book, which is like the ultimate—that’s the thing that can provide you with the deepest and most satisfying experience out of everything I’ve done, but at the same time, it’s the hardest to access because maybe you need to buy it, then you need to read, like, 180 pages to be able to finish it.

You have such a strong online presence, how did your book tour go in terms of meeting people IRL (In Real Life); did people have certain expectations of you?

Some people had no idea who I was and some people knew me from online a little, so it was kind of perfect that way. I was away for a month and I did Canadian book festivals that were booked by my publisher, plus dates throughout the US that were pretty much self-booked. I just asked internet writer friends, ”What would happen if I were to come to Chicago, what would happen if I came to this place?” and usually someone would be like, “Oh yeah, we can book this bookstore, we’ll put together a thing, or I know this guy who has a reading series, you could read there and stuff.” Some of it in the US was just right place, right time, so it was kind of a fluke.

It’s always interesting for me, especially when I am in the US, to meet someone who doesn’t know me at all. It’s like I have to explain my entire life story. It’s like, “Oh, so you’re French-Canadian, you have this weird accent, your name doesn’t make sense at all.” Sometimes no one knows how to pronounce my name. I feel like when people are aware of my internet presence a little, it’s easier in terms of skipping the entire life story phase and just going directly to being human beings. A lot of the people that I stayed with on this tour weren’t people I had met in person before, but it was very effortless to socialize with one another because we had already pre-lurked one another online, so we kind of knew what to expect from the other person.

How different was this book tour from a regular one, in terms of the actual events themselves?

It was weird because this was both a regular and a not regular book tour. When I was doing festivals things, I would usually have a hotel room and everyone would be very nice to me and I would get to wear this badge that says, “AUTHOR” along with my name on it, so if I am walking in the hallway of the hotel, people would talk to me and ask me questions about my art practice and stuff. So you’re very well treated when you do festivals, but when you do self-booked dates in a bookstore or something, you usually have to find a place to stay and you don’t get much beyond whatever proceeds you make from selling books. It was interesting to be able to compare both. There was this thing in Kingston where they got me to talk to teens, which was secretly amazing, like the teens were really into it. So I felt validated coming out of that, and the way other people were talking to me during the festival, I felt like I was starting to take myself seriously a little, like, “Oh, I am a big shot author now.”

But then I left Kingston to go to Toronto and I took this Megabus overnight, so I slept on the Megabus a little and when I got into Toronto it was 4 am. I didn’t want to bother anyone, like, “Hey, can I come sleep on your couch, would that be okay?” So I found this cafe that was open 24 hours and I just stayed up. Then, around 11 am, I started crashing, and I still didn’t want bother anyone to ask them if I could sleep on their couch, but then I realized that there was this small park right next to where I was, and I figured, “I could just nap in the park.” It was a beautiful day, and it was the park that’s behind OCAD, so just student types and people meditating and stuff. I ended up sleeping in the park that day and it was such a great ego reset, to go really quickly from being a moderately successful author taking myself seriously to being a homeless person sleeping in a park. It was pretty good in terms of remembering that the festival stuff is definitely not my normal life. Some of the readings I did outside of the festivals as well were a little less formal, like it allowed people to go insane a little more. There was this writer that I read with in Seattle, her name is Angela Shier. She had brought a piñata with her and she just smashed it at the end of her reading, which I thought was funny.

New Tab is semi-autobiographical and deals a lot with mental health—have you run into literary criticism that psychologizes you as the author?

A little bit. It’s funny to read comments on Goodreads or something, and people are kind of like, “Oh, I used to be like that guy, but that doesn’t mean I want to read about it, it’s not exciting.” There are two sides to that; one is like, well, what would have been “exciting” to you in this context? Do you mean car chases, because that probably goes against what I was trying to accomplish, so I understand where you’re coming from, but I can’t really accommodate you at the same time. Or do you just mean “everyday life” being more exciting? What would that look like exactly? It’s always weird to get comments like that because, what’s your definition of exciting? I am interested in that. It’s very difficult to anticipate what a piece of text is going to generate in someone else’s imagination, and I always feel stimulated by that, when it’s a type of comment I haven’t heard before.

The psychology thing, I do get people writing reviews of my book that sound almost like life advice or something, and I don’t always agree with it, but at the same time if that’s your response to it, then that’s your response to it. I can’t argue with the fact that this is your response to it. In the end, you’re always free to agree or disagree with criticism, and I try to remain open-minded and integrate what I think is good and leave out what I think is bad. Some authors say, “Never look at your reviews.” I am not that. I want to read every single one of them and I want to remain stoic in front of them, if possible. So instead of being emotional about a review, I try to look at it from a neutral point of view, like, “Ok, I see where you’re coming from, is that what my text really generated for you, is there something I could have done that would have pleased you more as a reader?”

Did you run into a lot of challenges in trying to write anxiety?

Self-deprecation probably isn’t the hardest part of writing for me. It’s not like I am doing stand-up comedy or something, like “have you ever noticed…” I am not making fun of someone else, I am just making fun of me, and I can pull that off, I think, because I am speaking from a place of knowledge, the same way a scientist could be talking to you about a complex science formula or whatever. I am talking about what I know, and it comes from having a strong internal dialogue and having felt miserable in social situations before.

If you’re someone who struggles with anxiety, low-stakes situations are high-stakes by default.

I totally agree with that. I feel like my anxiety was definitely really bad, especially around the time period in which New Tab takes place. The thing is, I wasn’t proud of myself as a human being before I started doing the writing thing, like the person I wanted to be versus the person I was just wasn’t in sync, and that would affect my self-confidence and self-esteem. I still have issues where if I go to a thing alone, I definitely feel anxious, like I’ll make excuses in my head to get out of the anxious situation. Last year, when I was living in Toronto and I knew less people, I definitely ran into new anxiety problems just from going to things and not knowing how to interact with people there. The social rules were a little different from Montreal, which was kind of good. It’s not necessarily bad for me to confront my anxiety.

Do you think that teens make up a considerable part of your audience, at least late teenagers?

I don’t think of New Tab as a [Young Adult] novel or something, but I wrote it in a style that’s minimalist and simple because I wanted it to have that kind of quality, easy to grasp and access but still has depth. I wanted the book to have enough depth so that an adult who isn’t me and who has read a million books could find meaning in it, but I also wanted the barrier of entry to be low enough so that someone who doesn’t think of himself as a reader could still enjoy it. I think teens should read whatever, including YA and not YA.

When we were talking in Kingston, the other writer on stage with me was a poet who makes poetry out of some of her friends’ Facebook statuses. She had this one poem about stealing from your workplace, and after she read it, I just asked her, “Is that something you’ve ever done, stealing from a workplace?” She was kind of like, “Well…” So I just turned to the audience and said, “I just want to establish that we’re excellent role models for you guys.” Then we started talking about what it’s like to work in an office and the brutal monotony of having a day job, and I kind of paused and I turned to the audience again and said, “Oh wait, that’s not the present for you guys, that’s your exciting future.” So maybe teens won’t be able to relate to everything in my book, but as long as they find something that they feel is pleasurable in there, then that seems good to me.

I often use humour as a mechanism to encourage the reader to keep reading, but humour is like Sriracha for me, it has a very strong taste. If you’re not careful, it can drown everything else out. I want humour to be just one mechanism inside a bigger thing, like, it’s funny but it’s not only funny. I also want to be a good role model towards a potential teen audience, which is tricky, because how do I write about stuff like casual drug use and at the same time not be a shitty role model? It’s a hard relationship to navigate.

Can you tell me about your work with Metatron?

Sure. Metatron is Ashley Opheim’s press. It started with a grant from Jeunes Volontaires, and now it’s moving beyond the grant stage. There’s a second batch of Metatron books that will be out probably late November, and it’s getting to a point where its more work than Ashley can handle by herself. With Ashley, we’re very used to working together, because we’re constantly involved in one another’s projects, so it’s very easy for us to collaborate on something.

Ashley asked me to be the main editor on Marie Darsigny’s collection of poetry. There’s a few reasons why I said yes. I like Marie as a person and a writer, but I also like how she’s French-Canadian but she writes in English, like me. There’s a weird synergy there. Also, Marie’s poetry has poetic qualities, but it’s not abstract poetry. It’s very straightforward and the focus is much more on strong statements and capturing certain feelings precisely than it is on playing with language or something, so I felt very comfortable working with her. I’m getting involved a little bit more with Metatron, but it’s still very much Ashley’s thing. Through Metatron, we publish a lot of writers who are in their mid-twenties or something, and it’s usually the first time that they’ve been published at something close to the book level, so it gives them a path to bigger projects. The books aren’t necessarily meant to be a full meal, they’re more like a taste of what this person can do.

A good introduction to that writer’s work.

Exactly. So that’s the vision for it, and it’s fun to be able to work with writers at that level, because to me it seems really exciting. It’s like being at the forefront of something, I am excited to see where the Metatron writers will be, like, five years from now. For the upcoming Metatron books, we’re doing Marie Darsigny’s book, a book of poetry by Olivia Wood’s, a funny book of poems by Jason Harvey, a short novel by Jasper Baydela and a book of poems by Julian Flavin.

What’s next for you?

I don’t know. We’re be putting together live events that we’re presenting as Metatron. On my own, I started working on a new giant thing, which is probably going to be a novel. I want to do “better” than New Tab, but it’s like, what do I even mean by that?

Car crashes.

Yeah. Car crashes, bombs, terrorist attacks, Ebola, all that stuff. Right now, it’s kind of a nightmare to work on the new thing, because every time I look at it, I’m just like, “Why am I doing this to myself?” But then I can’t help myself, so that’s why I am doing it. Does that make sense? Am I making sense?