Resilience, Empathy, Elegy, and Eco-Awareness in Meg Eden’s Drowning in the Floating World: A Book Review by Zoe Shaw

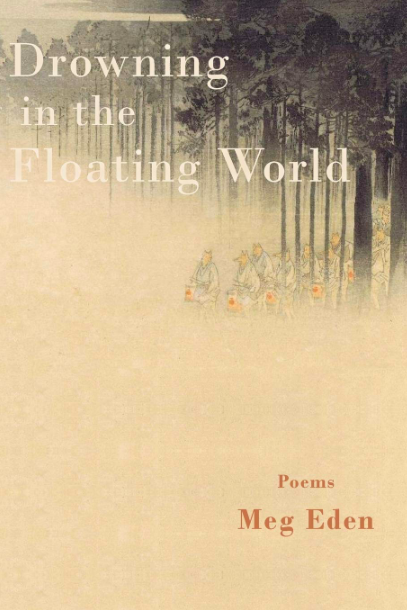

Book Review: Meg Eden’s Drowning in the Floating World

Meg Eden’s elegies to victims of 3/11, the ecological disasters that occurred in northeast Japan in March 2011, are inspired by real people or imagined completely. They recover the domestic, urban, and nonhuman experiences resulting from the Tōhoku earthquake. Eden makes memorialization a collective task via extensive research that enriches her characters and settings to cast readers as witnesses to the horrors of the repercussions of environmental crises.

A variety of histories and subcultures distributed among multiple poetic forms rejects the representation of stand-ins for a single version of Japanese culture.

Drowning in the Floating World is only 80 pages tightly packed with a wide and nuanced range of lives that intentionally overwhelms the reader.

Eden makes these figures real; you are called to feel powerfully with every poem.

Drowning opens with “Hokotashi City, Ibaraki Prefecture,” where crescendoing couplets carry fifty beached whales to shore and expose us bluntly to the ecological horror that precedes the impending tsunami:

People still surf but how can they ignore

the fifty bodies, like tea leaves

at the bottom of a scryer’s glass,

heavy and loud in memorial?

The aquatic nonhuman—ocean and whales alike—demands human attention to the devastation to come. The witnesses of the whale ignore or repress the warning, avoiding the inevitable. Nature throughout the book is “heavy and loud in memorial” as the human and nonhuman suffer in tandem during the tsunami and the resulting Fukushima nuclear disaster.

After the tsunami destroys ways of living on land, the trajectory of the book brings us into the lives of humans, dogs, cows, foxes, machines, and mythologies whose beings are intertwined and alienated at once by the natural disaster. “Town Hall” is one of many poems where the speakers empathize across species to articulate the tsunami survivors’ collective grief:

Watching the town resurrect,

I remain unfixed,

mouth filled with birds.

My eyes are dusty & split

down the middle; my bowels

washed in mud. A car

rests in my intestines.

The dog in my chest

just delivered puppies.

Here the human metaphorizes the nonhuman, and the reverse occurs in “Fukushima Syndrome” where a group of dying cows mourns and resents the departure of their owners: “From our stalls, we can see the world / they’ve built fall apart.”

The cattle and their owners record their thoughts of each other in stanzas that are dated from the tsunami to a year later, marking the effect of the nuclear disaster across time to their shared and separate lives.

Births, deaths, and rebirths weave this multitude of histories together, grounded in images and detailed characters that resist making trauma abstract. “Villanelle from an Okawa School Mother” features a woman who finds her daughter’s headless body in the ocean. Her daughter “carries inside her a body of water,” literally drowned in the ocean and preserving the memory of the tsunami and the lives that it destroyed. The book closes with the transformation of the same water into a source for “Baptism,” for life and rebirth: “Strange, this water: the same // that buried five cities.”

Despite the hopelessness of many speakers in Drowning, they frequently try, and sometimes succeed, to reach a point of forgiveness between the different forms of life that have suffered at the hands of ecological disaster.

Perhaps it is crisis that brings us together all the while dividing us.

The last poem in Meg Eden’s Drowning in the Floating World ends on an uplifting note, but the book continues to remember the victims of 3/11 beyond this final line. Eden does not rely on her personal history with Japan as cultural knowledge; she provides in the notes a plethora of resources and further reading as well as intertexts from the epigraphs, which include Masashi Hijikata and Shuntaro Tanikawa.

Drowning is ultimately a harrowing read that provokes action in its reader and, at the very least, has made you a witness to the horror, and opportunities for resilience, that result from Japan’s 2011 ecological disasters.

——————————————————————————————-

Drowning in the Floating World was published by Press 53 in March 2020 and is available to purchase now on their website.

carte blanche has published earlier versions of “Coming Home after a Tsunami” in 2015 and “I Ask My Mother What It’s Like, Living at the Bottom of the Ocean” in 2016.

ABOUT ZOE SHAW

Zoe Shaw is a writer and editor living in Montreal. She is about to receive her master’s degree in English from McGill University. She is Managing Editor of carte blanche.

Photo by Nilufar Mokhtarian

ABOUT MEG EDEN

Meg Eden’s work is published or forthcoming in magazines including Prairie Schooner, Poetry Northwest, Crab Orchard Review, RHINO, and CV2. She teaches creative writing at Anne Arundel Community College. She is the author of five poetry chapbooks, the novel “Post-High School Reality Quest” (2017), and the poetry collection “Drowning in the Floating World” (2020). She runs the Magfest MAGES Library blog, which posts accessible academic articles about video games (https://super.magfest.org/mages-blog). Find her online at www.megedenbooks.com or on Twitter at @ConfusedNarwhal.