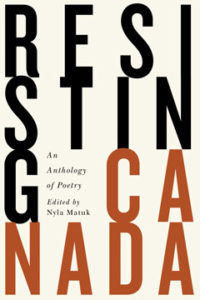

In November of 2019 I spoke to Nyla Matuk about colonialism, activism, and resistance poetry for the Fall issue of the Montreal Review of Books. Matuk’s book, Resisting Canada, was just about to come out from Véhicule Press, and I for one was excited to see such a revolutionary book in the Canadian literary milieu.

The book is beautiful and searing, an anthology of voices championing defiance against a settler state that silences and abuses its population while simultaneously praising itself for its image as a progressive and liberal melting pot.

There is never a bad time to honestly discuss Canada’s oppressive tactics and colonialist heritage. But right now, as the federal and provincial governments, RCMP, and Coastal GasLink/Transcanada flagrantly violate Wet’suwet’en, Canadian law, and international law, it feels particularly relevant. To quote Erica Violet Lee, the land defense currently being carried out is “an enactment of Indigenous law and an affirmation of Indigenous life.” As we witness Canada’s assault on Indigenous rights, we must take action.

You can read my full review of Resisting Canada: An Anthology of Poetry on mRb. I hope that after reading both these pieces, you will make full use of the Wet’suwet’en Strong: Supporter Toolkit to use your privilege to take part in actions and events in your area, email and call your representatives, and donate.

The title of this piece references lines from “Giving a Shit,” by Janet Rogers.

Marcela Huerta: I was so moved by this book. It’s not an understatement to say that Resisting Canada: An Anthology of Poetry is a game-changer. This book slices through the Canadian narrative of exceptionalism and the concept of the “melting pot.” I’d like to have an expanded understanding of how you came to the process of editing it.

Nyla Matuk: Véhicule Press had approached me to suggest that I take on this project, which they had conceptualized to an extent with the help of the poet and professor of literature Sonnet l’Abbé. Out of that, I landed on the idea of resistance, which isn’t a genre in the sense of a marketed, capitalist genre, but could be used to stand for literary expression of political will against, e.g., a settler-colony. You do see resistance literature in a lot of the work of the Global South, and in liberation movements, and anti-colonial narratives, and anti-colonial literature/cultural theory. Of course, there is a whole body of scholarship and literature that is no longer about using the “post-colonial literature” label, that looks at Indigenous peoples and resistance to the state. So that was where I turned as I started to look into various objections to the Canadian state.

MH: It’s so important to force the Canadian state to reflect… not reflect, reflect is the wrong word, because the concept of reflection implies a past, it implies actions that are done and no longer happening. To answer for their actions. But having to answer is something that Canada refuses to do. It tends to go for half measures.

NM: There is the accountability factor, supposedly embedded in ‘truth and reconciliation,’—which of course is an official term—but to use it instead as small t truth, small r reconciliation. In other words, a real operationalization of that hasn’t happened yet, and it’s a bit of an empty label a lot of the time. We saw that most recently when the Report on the Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls was published in June. The reactivity to it, in the mainstream media, the defensiveness against characterizing the murders a genocide, for instance… all of that is denial, and denial is a major feature of settler-colonial states. The policies are maintained and continue—the Indian Act is still in use, for example. It just goes on and on. I think people don’t really pay attention to statecraft, they don’t pay attention to the strategies around statecraft which, by and large in Canada, involve dispossessing and continuing to colonize Indigenous peoples in the service of a neo-liberal model of economic growth; the need to compete on a global scale and to continue to grow the economy of the industrial state. I’m not saying anything new here; the denialism around this is expressed in various ways in the poems. They’re a resistance, and it’s a resistance to point out the lies and the denial, these “national fairytales”—to use Alicia Elliott’s phrase.

MH: The work is there. The work is being done. How are we complicit when we remain passive?

I thought a lot about the education system while reading this—of course many of the pieces speak about residential schools—but thinking also of the educational system in Canada. When I think about what I learned when I was in school, I never saw a single book by a BIPOC author on the syllabus. Unbelievable. And I think about this book and how much of it is education through art.

NM: To compare this more critical poetry to the typical product of poetry publications in Canada that might be about personal issues or even different kinds of subjects for poetry that don’t have a political angle necessarily (though of course everything is political) this work is much more urgent in its tone. People often object to poetry that is perceived as having a message or trying to tell you what to think/feel, but I don’t think that always turns out as the “bad poetry” tastemakers (whomever they are!) want to corral into that category. There’s tons of poetry that doesn’t tell you anything at all: is someone’s epiphany that, the way the light is angled on a peach in the fruit bowl one Sunday afternoon has allowed them to understand their father’s suicide also telling you what to think/feel?

The book will challenge what “Canadian” literature is, will expand whatever we want to ascribe to a national literature (though it seems to me we can speak of First Nations as nations but Canada only, at the moment, as a ‘state’) and it’s a way to look at a “history from below.” Actually, it made me wonder why literary output is anthologized according to state–why Canadian? Or Australian? Yes, we could say these poetries assemble common elements like climate or landscape or historic events, but how important are those commonalities when we think through the real history of the state, its colonization of hundreds of First Nations? Features of geography, historic events, and so on do not “belong” to official history.

Think, for instance, about The Journals of Susanna Moodie, by Margaret Atwood, and Susanna Moodie’s work itself, all about being a settler, and what it involves. I was amazed to find, when I was looking at it on the Poetry Foundation website, that there’s a long entry by a Canadian academic on Susanna Moodie, and one of the ways he described what she was talking about at the time was “the uncivilized land,” and this is again a mentality of: “Oh, well it was uncivilized, bad weather, and savages…” That sort of narrative is what we keep hearing in the literary discourse—whether it’s literary criticism or cultural criticism or, I don’t know, the Globe and Mail’s egregious opinion writers urging us to use caution when deploying the word ‘genocide.’ What about ‘history from below’? It’s something Resisting Canada tries to tell. There were hundreds of civilizations here before European settlers came and tried to kill them all off and get rid of them. So this is something to be aware of–the very casual use of this word, ‘uncivilized’ in the middle of this entry on Susanna Moodie. I thought: “Oh, is that what Susanna Moodie said? Did she also think of the place as uncivilized?”

MH: We must look at those colonial and racist turns of phrases that become a part of the fabric of this country and become aware of the way that we talk about this country. How can we shift those perspectives? I thought about how much time came up in this book. This idea of timelessness, and linking it in to the urgency we were discussing, I felt so much time in these. In Lee Maracle’s “Streets,”

to raise my voice in resistance

to the desecration of your eternity.

and then in “Remembering Mahmoud:”

there is no tomorrow in yesterday so let us advance

There is a lot of existing in the past, present, and future. It’s unbelievable to me how much more time the scope of the world contains when we think of Canada outside of a colonial lens. All of a sudden we are adding thousands and thousands of years and looking more at the concept of the Earth not as something that belongs to us but that belongs to who is coming next. These shifts in the ways that we think about the climate, the land… it’s interesting to think about that quote you mentioned: “uncivilized lands.” What are we doing to try to unlearn, to try to shift the way that we look at everything surrounding us?

NM: In Lee Maracle’s book My Conversations with Canadians, she quotes an artist who says “`It’s not how we fit into you, it’s how you fit into us.” You are a chapter of this, you are the colonizer at the moment, you were the colonizer 200 years ago and 300 years ago but there are different phases to all of these colonizations. You see this in other contexts, for instance the carving out of countries by the French and the British when the Ottoman empire fell: new colonizers replacing 400 years of the Ottoman Empire. There are millennia of toponyms and archaeology establishing the presence of indigenous people in those regions. Other examples are Ireland, Rhodesia, Algeria. There are these timelines of division, renaming, and settler arrival, but the Indigenous People have always been there. It is a fundamental feature of decolonization to have this very crucial understanding of the passage of time and history. I think in a lot of the poems, hope and time are bound up together. For example, in the poems about Mahmoud Darwish, by Lee Maracle. Her dramatic monologues have him talking about the past, present, and future. Again, that is part of the consciousness around colonized people’s ideas included in the anthology.

MH: And this idea of intergenerational trauma, of carrying it within these expanded timelines, not looking simply at the experience of Canada through the colonizers, but looking at the effects in the past on Indigenous Peoples and in the present, and in the future. It made me think of the Asociación Madres de Plaza de Mayo—mothers from all walks of life who campaigned for their children, the civilians who had been “disappeared” during Argentina’s 1976–1983 dictatorship —and one of the concepts of their movement was that when someone was disappeared, there was no body, therefore there is nothing to mourn, there is just a constant state of grief. The disappeared become a spectre that lives, that haunts in the present. It made me think of `Rosanna Deerchild’s “mama’s testament.” Looking at the idea of sharing your story, what does it mean to do that when the trauma is so present, it exists not only in you but in your legacy? What does it mean to share stories when someone may not be able to share their own?

NM: Archival records of oral history are important so for that reason, I included that poem too, and again, it ties into the idea of ‘history from below.’ It’s not just psychological trauma, of course – that’s the sort of au courant term that we’re hearing a lot in the Canadian media – but you also have to think about the de-development of the societies, the more pragmatic setbacks of colonization beyond the psychological trauma and the intergenerational trauma. The fact that the Indigenous Peoples that have been colonized… they have not been allowed or able to continue their traditional ways of life. Leanne Betasamosake Simpson has an essay on going into the woods and the practice of tapping on maple trees for maple sap. There are so many of these teaching stories that recount these traditional ways of life that have been so often cut short or ruined. But Simpson insists on belonging, on agency, on presence.

When I was growing up, as you were saying earlier, it was a big whitewash, there was very little in our textbooks about Indigenous Peoples. They were historic, over with, not living in the present.

MH: We didn’t even learn about internment, the word was never even mentioned.

NM: No there was nothing, this history has been buried.

MH: I find Canada has a simmering racism, and the nation is terrified of it boiling over. And I know what you mean, it’s always disappointing to see people think they are being very progressive. And that Canada is very progressive. We’ve been taught, “we are the good neighbour,” and “we’ve been doing everything right,” and we’re not.

NM: I never really thought so.

MH: When I was reading this book, I felt so much of its importance would lay in it being used as an educational tool. El Jones’s poems, for example, are so vibrant and informative—these are different ways of learning, that we still haven’t explored in our educational systems.

NM: I hope that this will offer an opportunity for people to discuss this, to discuss poetry as news. Many of these poems open up worlds of information and history, and they lay bare the injustices perpetrated by the Canadian state. What it boils down to is that people will either be moved by the injustices that are made evident in this work or they’re going to sit there and try to justify the state. My working assumption here is that no state has the right to exist. Only people have that right.

MH: I’m wondering what it means to resist through poetry, what it means to resist through art. That is something that is incredibly pertinent to me in my life, thinking about the Chilean coup that displaced both my parents, and Chile’s artistic forms of resistance. The “Nueva Cancion” movement in Chile, for example, the fact that some of the first people to be killed during Pinochet’s dictatorship were artists, were poets, were singers….I think that it poses a huge threat to the establishment.

NM: That’s right, it’s much more powerful than people realize. The book that I’m publishing in Canada today, this book, under the wrong regime would get me arrested. And get Véhicule Press shut down. But the Canadian government supports regimes around the world that jail writers. They are considered dangerous because they are challenging and refuting the ideology of the neoliberal state, they are resisting imperialism, they’re calling for decolonization, for nationalizing their industries (oil in Venezuela, and Iraq, for instance) and throwing off the shackles of these capitalist regime-change agitator states like Canada and the U.S.

MH: Yeah, and empathy is terrifying to the ruling class. When the public can be moved by the feelings of another human being who is speaking out in a way that can reach the masses.

NM: That too, it’s very much about challenging, demystifying, and disempowering the ruling classes.

MH: Of course, it’s so demoralizing, it’s so depressing, but at the same time, I think that work like this does instill hope in the future. It takes a stand, and it’s so clear that the people that are featured are not going to stop resisting. It’s incredibly inspiring. I think that it shows us what we can do and how much more we’re capable of.

NM: It’s trying to redefine. The idea is to redefine what the national identity has been, to question everything, and to find that in our questions there are ways in which justice might be served. It’s just that here, there is this, as Lee Maracle has pointed out, phony veneer of decency and politesse and civility… one of the worst things is the application of civility to every kind of discursive practice. Civility is what shuts people up, tells them that they can’t be enraged at what has been done to them. And it’s only the privileged class that insists on civility.

Nyla Matuk is the author of two collections of poetry: Sumptuary Laws, and Stranger. Her poems have appeared in magazines and anthologies in the Canada, the U.S. and the U.K., and her work was shortlisted for The Walrus Poetry Prize and the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award. In 2018, she served as the Mordecai Richler Writer in Residence at McGill University.

Marcela Huerta is the author of Tropico, a collection of poetry and creative nonfiction published by Metatron Press in 2017. Her work is featured in vallum, Peach Mag, Leste, ALPHA, Bad Nudes, Montreal Review of Books, spy kids magazine, CV2, and Lemon Hound. She is the Poetry Editor at carte blanche magazine.