carte blanche statement regarding Gwen Benaway, originally published via Twitter on June 16, 2020

“As a venue that has promoted and published Gwen Benaway’s work, we feel it is important to share the following call for accountability regarding discrepancies about Benaway’s Indigenous heritage:

We had been unaware of these claims until recently and take them seriously. We would like to extend our apologies to any Indigenous individuals and communities that have been directly hurt or affected by Benaway’s inconsistencies.

We are sorry for any harm that publishing and championing her work on our platform may have caused. We want to make space for those individuals who have been affected and we want to support them.

We can always do better and we hope that Benaway will take the time to address the concerns of the Indigenous and literary communities at large.”

BEING ASKED TO WRITE about the status of Canadian Literature feels very similar to when an ex lover asks you out for coffee. You know nothing good will come from it and can anticipate the entire conversation, but you still show up looking cute and hoping that therapy has finally fixed them.

At least, that’s how talking about Canadian Literature feels to me. I’ve been there, had the group therapy, learned to love myself for myself, and have deleted CanLit’s contact information from my phone.

After all, the disconnect between the people who live in Canada and the writing which CanLit champions is wider and more ice laden than Hudson’s Bay.

***

If Canadian Literature had an OkCupid profile, it would feature a photo of a bearded white guy at his Muskoka cottage. You’d scroll through his profile, rolling your eyes at his smug references to ice wine and “chilling with like minded people.” His profile would be the kind that I instantly label as “fuckboi.” In other words, the kind of guy who strings you on for months and then texts to say he’s “just not that into it anymore.” And if you’re very lucky, he’ll have an in-person conversation where he will drop the words “emotionally unavailable” and say he just “wants to do his own thing.”

Canadian Literature, otherwise known as CanLit if you were born in the 80s and beyond, is a loose cluster of marketing terms. There is an established canon of great Canadian writers, most of them white and all of them close to death. Some CanLit writers are writers I admire, such as Alice Munro, Timothy Findley, and Al Purdy. Some CanLit writers are writers that I don’t admire, like Margaret Atwood, Joseph “he should not be named” Boyden, and Ken Babstock. By and large, the entire collection of CanLit writers replay the same tired Canadian clichés over and over again while CBC Radio drones on like a comatose PA system: Up next, an exciting novel about mid-19th Century Ontario where an introverted white woman struggles over her abusive relationship with a fur trapper who may or may not be her cousin.

I’m oversimplifying for comedic effect, but at least I’m trying to be funny. Humour is fatal to CanLit— unless it’s the kind of humour which only five people can appreciate at a dinner party and everyone else is stuck tittering nervously. CanLit is a slow moving Via Rail train, lulling under signal delays and faulty wiring. Sure, the scenery is occasionally pleasant to look at and the drinks are free, but you’re not watching or drinking. You just download American television on your iPad and send your ex passive aggressive texts until you reach your destination. This feels like an apt metaphor for how readers in Canada, the actual weirdoes who still buy books and show up to events, feel about CanLit.

It’s there, we see it, but are we happy? We’re trapped in bad relationship with our needs unmet and our expectations crushed. Every new release season, we hope CanLit will finally show up and be the boyfriend we’ve always wanted. Does CanLit even care about our carefully curated dreams and laughing couples’ montages?

No, not for a millisecond.

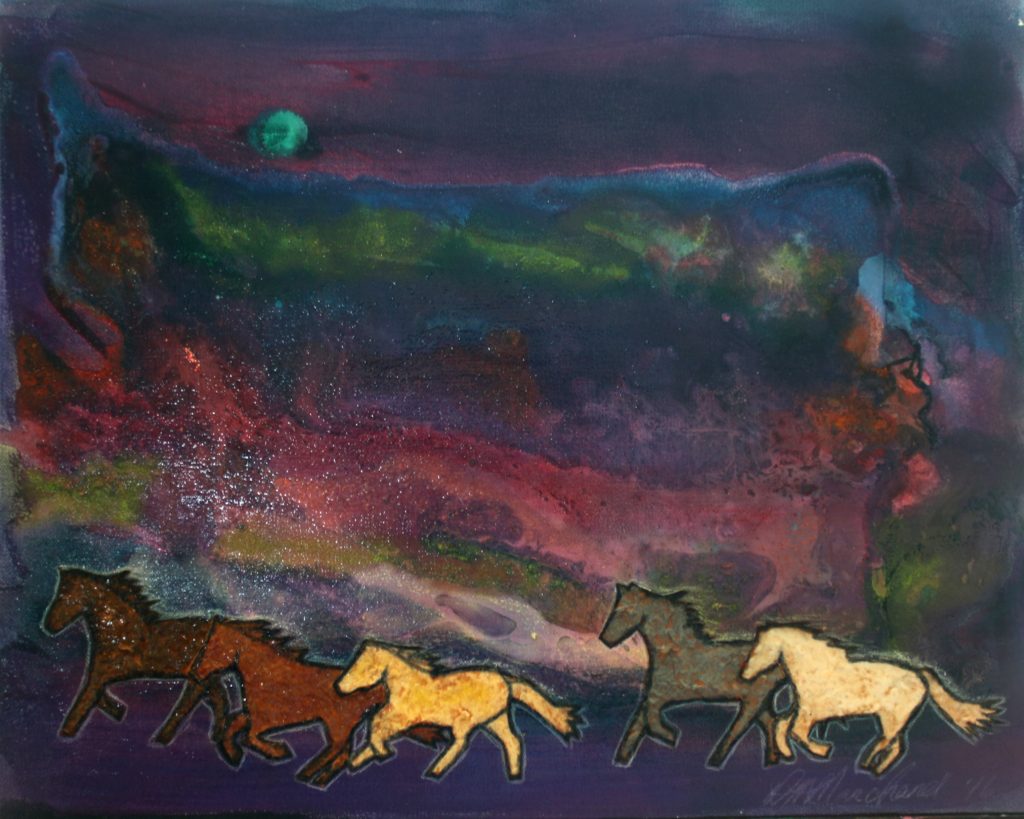

Sky Ponies #48. “This series is about my personal healing journey. At a difficult time in my life, I started painting these abstract skyscapes because it was all that I could paint. I put horses through them because I was remembering a story I was once told about horses in the sky. It was these stories and horses that helped me to move forward.” Dawn Marie Marchand.

***

CanLit cares about CanLit. But similarly to how Canada feels about this monolith, CanLit doesn’t much care for Canada. For a country that is diverse and expanding, our literary output is as tepid as Tim Hortons’ Dark Roast coffee. Indigenous voices get drowned out by found poetry about long dead Arctic explorers. If you’ve heard any Canadian poetry in the last five years, you know who I’m talking about. If you don’t, you’re probably well-adjusted and should skip to the last paragraph of this essay. In the poetry world and beyond, there is the usual infighting about young voices, Queer voices, and voices of colour at conferences and in magazine editorials as well as really serious literary discussions happening in Banff, but not much changes in the literary landscape. CanLit shrinks every year as its adherents die out. Like a house party at three a.m., everyone is leaving, having bad sex in the alleyway, or regretting showing up in the first place.

***

I am excited about the backlash from this essay. When two people tweet their indignant response to me on Twitter, I’ll be ready with a handful of GIFs and some much needed trans girl sass.

I’m not the kind of girl CanLit is looking for. Like on dating apps, I’ve gotten good at knowing when my particular brand of Canadian identity isn’t wanted. Sure, CanLit is happy when I write about gender and reconciliation within Indigenous communities, but if I write about giving blowjobs to straight boys in a TTC washroom I suddenly find myself on the CanLit “do not call list.” I’ve started turning down the frequent requests from media and literary publications which start with the lines “hey, we’re doing this think piece on [insert gender/Indigenous voices] and we’d like to have [unpaid commentary/your voice] in our [edited by a white cisgender person] publication coming out in [unclear timeline].”

My voice is my voice, not an Instagram filter to highlight your progressive politics. Just like the boys I meet, CanLit only values me for how I look in photos, not for my mind.

CanLit marginally embraced my writing when I transitioned, as I was becoming one of a dozen trans women authors in Canada, but only as far as it was a good thought piece. Please, CanLit implores, write more about the sad and traumatic experience of transitioning, but can you edit out the anal sex bits? Not that I’m not grateful for the exposure these pieces give me and my writing, but they force me to choose between economies of harm. Writing these pieces helps pay for the very expensive reality of my transition, but publishing them draws the attention of alt-right racists and transphobes on social media. My favorite side effect of being a published trans girl writer is when one of the guys I’m sleeping with googles me and ghosts like Stephen Harper after his election loss. All the while, the placid CanLit community scrolls through their newsfeed, muttering “Oh, how shocking? A trans girl writer in Canada. What’s next, a hockey goalie from New Brunswick who decides to move to Montreal to follow his dream of becoming a master poutiner?”

***

Some passive aggressive (Canadian) readers are likely asking what my advice is to transform CanLit into something meaningful for Canadian readers. But we know the problems in CanLit as we’ve been talking about them for more than thirty years. My perspective is that CanLit is pretty much the same as the year-long relationship I had when I first transitioned. He was a nice enough guy with some good attributes, but he just didn’t want to deal with his shit about gender and sexuality. He dealt with it by saying and doing transphobic stuff to me, but continued to play-act being a supportive lover in public. I was caught in a loop of feeling inadequate, trying to prove my femininity to him, and letting him get away with some truly bad behavior. I made him feel transgressive and he made me feel loved, but neither of us was actually getting either of those things.

To me, CanLit is that ex-boyfriend and my part in CanLit is every racialized, Indigenous, Queer, or marginalized writer in Canada. We’re here to give CanLit street cred, to be the Other in their dance of whiteness and desire. We’re the ones who do the work and stroke the egos, waiting around for the moment when our boyfriends/CanLit finally love us as we are.

We’re, as marginalized writers, trying to fix CanLit by working harder to be amazing.

We let CanLit devalue us and do some majorly oppressive things to us while propping it up with our dollars and time. CanLit uses us to feel cool at parties (oh, look a new South Asian writer! Take that, America) but doesn’t follow through on their outward radical politics. As I eventually realized in that relationship, diverse writers in Canada need to wake up and understand that we’re already better than CanLit.

We’re interesting, brilliant, and boundary pushing.

***

Without us, CanLit is just another straight guy with a fear of intimacy and a self-aggrandizing image of success to project. It’s time we cut the cord and implement the “no contact” rule.

What am I suggesting?

We need to step out of CanLit to fix CanLit. It’s time to let CanLit work on their own issues without us to prop them up. We need to not respond to CanLit’s vague texts or send them our own “why don’t you love me?” messages. We need to not subscribe to The Walrus or other CanLit publications which are not diverse. We need to stop entering their writing contests, going to their readings, showing up to their events, or buying their books.

Try this. Make a rule not to buy books by white Canadian authors for an entire year. There are many diverse authors living on this land to support instead. Back away from the doomed relationship you’re ensnarled in and start a new one with writers and publishers who reflect the actual reality of Canada.

Prayers for My Sisters. “This series is about recognizing that within the issue of MMIWG, the women are cared for spiritually. They are prayed for and ceremonies held for them. The red background pays homage to the work done like ‘The Red Dress’ by Jaime Black which has raised awareness since 2011. The 12 sticks represent the lodges and the ribbons represent the prayers. I have supplied an image of a painting and also the installation, which allows people to interact with the piece.” Dawn Marie Marchand.

***

I’m not saying this to be cruel. As much as I’m sick of CanLit’s crap, I get why CanLit has the issues it has. It had a rough childhood and no one asked it over for sleepovers. CanLit’s parents were political parties who flip-flopped on arts funding. They gave love and then took it away for no reason.

CanLit has avoidant attachment. It’s anxious. It hates itself. American Literature bullied it. Some might say, let’s have compassion for CanLit; let’s mourn its potential. But none of this excuses CanLit for its bad behavior.

I sincerely believe the only way to rehabilitate CanLit is to break up with it.

Maybe CanLit will change and grow as a person once we walk away. Maybe CanLit will die a lonely death, phoning us at three a.m. to leave angry voicemails.

I don’t really care anymore and you shouldn’t either. Let’s focus on us. Diverse Canadian writers, welcome to the future. We can go to our events, promote our books, and build our networks. We’ve been doing it for decades. But now, instead of living off the attention crumbs CanLit has offered us, we can work on deepening our connections to each other, our communities, and our art.

***

The true cost of a bad relationship and an entity like CanLit is the same. We don’t grow. We miss out on the love we want and need to be fully actualized as human people. We spend our life in doubt: doubt of ourselves and our worth as well as doubt of the other party’s intentions. CanLit has had many chances to reinvent itself. For example, conferences about learning and growing litter CanLit’s history. But then those conferences are followed by CanLit doing abusive and dumb things like the recent issue of Write: The Magazine of The Writers’ of Union of Canada, a debacle of cultural appropriation, racism, and white fragility.

We, as diverse writers in Canada, deserve better. Instead of waiting for CanLit to change, let’s change our relationship with it.

***

Sure, we have some nice memories of moments shared with CanLit. They weren’t always bad. But is that enough to continue living inside this unproductive and vindictive relationship? Maybe other diverse writers are happy with the small payouts from the CanLit coffers. Maybe some of us don’t believe we’re worth more or can stand on our own.

I disagree with second guessing our value. Let’s see what CanLit does without our brilliance. Another novel about rural intrigue and family dysfunction? Excuse while I barf for twenty minutes into my Swiss Chalet sauce cup. Maybe CanLit will publish a writer under thirty and celebrate their work for two months before they franticly start spamming us with articles about The Handmaid’s Tale. Finally, CanLit has something to lord over the American monolith, a dystopian sci-fi epic which uses the actual legacy of racism and slavery as its subplot. As an added bonus, all the female characters hate each other and its author—who is also a producer on the adaptation for TV—is a sexual assault apologist who defends predatory men by claiming they’re part Native on Twitter. Good work, CanLit. You’re really making the rest of the world jealous. Or perhaps, like my ex with his cryptic close up selfies captioned in emojis, everyone just thinks you’re on hard drugs.

I can’t predict the future, but wouldn’t it be fun to see what happens if we cut off contact?

***

The truth is that CanLit, as a definable collective of writers, publishers, and literary works, is an imaginary kingdom of winter landscapes and habitant farms. Everyone within CanLit has a personal agenda, a regional focus, or a repressed loathing of the CanLit paradigms. We’ve been grouped together as a single category when we’re many distinct perspectives. It’s convenient for someone, I’m sure, but it’s not the truth of Canada or Canadian writing.

Who would we be without CanLit as a label? If we let go of our unhappy relationship and dared to be single, would our life collapse into a sad cycle of cats, ice cream, and self help books? I imagine the opposite would occur. The real brilliance of Canadian writing would finally be free to be happy as it is, without needing to tie back to this myth of a happy, multicultural mosaic of so-called Canadian identity.

People cling to CanLit because they’re denying something. For many white Canadians, they’re denying the history of genocide against Indigenous peoples in this country. There are other denials such as pretending CanLit’s Toronto- and Ontario-centric lens isn’t a thing, the erasure of Queer and Trans Canadian writers, and the denouncement of our experimental and radical writers. Underneath the label of CanLit is a literary world of oddballs, social rejects, and colonial resisters.

That’s a more interesting world to me than the one we’re currently pretending is our Canadian landscape.

***

Hence my advice for us to follow the “no contact” rule. Let’s take thirty days to read writing which defies our definition of CanLit. Explore small publishers in Canada, not the big boys in their condo towers. Don’t take your reading recommendations from major media publications. Start building an authentic connection to actual Canadian writing. Go to a small literary event, something without a gold star CanLit icon. Branch out, Canada, and see what happens.

Whatever you do, don’t respond to CanLit’s cries for attention. Mute them on Twitter. Unfollow. Block.

I know this is an unpopular suggestion. There are ardent believers in the politics of literary reform. I am not one of them. As a feminist, confessional, trans girl, Indigenous poet (wow, all the things), my job is to suggest radical alternatives. CanLit is breaking our boundaries. They don’t respect us as diverse writers. The only compromise is no compromise. Thirty years of discussion hasn’t gotten us anywhere. We have at least another ten years before the CanLit elite are dead.

Let’s not wait for them to get their business together, because we know they won’t. They don’t want to change.

Diverse writers in Canada, love yourself now. Love each other. Don’t be the token or the fallback for CanLit. Move forward, move on, and hey, maybe they’ll grow up. Either way, we’ll be better off and finally have a shot at the happiness we deserve.

My hot take on CanLit is the same as my hot take on Nickelback, “Who, them? They’re still making stuff? Gross.” Let’s take walk and let CanLit figure itself out. It needs to spend some alone, thinking about what it did wrong and why it’s not vibing with someone like us. Just like that guy we’ve been hanging out with for a year, we need to know when to quit. It’s just not working out as we hoped. It’s not us, it’s them. Break up, no contact, and look for literature that can love us as we need to be loved. We’ve helped CanLit as much as we can and like the classic Alanis song reminds me, they outta know.

Gwen Benaway is of Anishinaabe and Métis descent. She has published two collections of poetry, Ceremonies for the Dead and Passage, and her third collection, What I Want is Not What I Hope For, is forthcoming from BookThug in 2018. An emerging Two-Spirited Trans poet, she has been described as the spiritual love child of Tomson Highway and Anne Sexton. In 2015, she was the recipient of the inaugural Speaker’s Award for a Young Author and in 2016 she received a Dayne Ogilvie Honour of Distinction for Emerging Queer Authors from the Writers’ Trust of Canada.

Gwen Benaway is of Anishinaabe and Métis descent. She has published two collections of poetry, Ceremonies for the Dead and Passage, and her third collection, What I Want is Not What I Hope For, is forthcoming from BookThug in 2018. An emerging Two-Spirited Trans poet, she has been described as the spiritual love child of Tomson Highway and Anne Sexton. In 2015, she was the recipient of the inaugural Speaker’s Award for a Young Author and in 2016 she received a Dayne Ogilvie Honour of Distinction for Emerging Queer Authors from the Writers’ Trust of Canada.

Dawn Marie Marchand is a member of Cold Lake First Nation and is a Cree and Metis Artist who is no stranger to Indigenous issues and activism. As a student of the Boreal Forest Institute, she met and was in studio with some great teachers and mentors who continue to influence her work. She has spent many years using her artistic abilities to work with at-risk youth through art integration, helping them express their knowledge, and creating safe spaces to confront and heal from trauma. She believes that art is a necessary tool to help people. It is essential to cultural survivance and revitalization.

Dawn Marie Marchand is a member of Cold Lake First Nation and is a Cree and Metis Artist who is no stranger to Indigenous issues and activism. As a student of the Boreal Forest Institute, she met and was in studio with some great teachers and mentors who continue to influence her work. She has spent many years using her artistic abilities to work with at-risk youth through art integration, helping them express their knowledge, and creating safe spaces to confront and heal from trauma. She believes that art is a necessary tool to help people. It is essential to cultural survivance and revitalization.