I struggled with this blog post. How I discovered… what? Poetry? Was it rhyming taunts on the playground, or “Kublai Khan” in Mr. Knight’s high school English class at Magee Secondary in Vancouver? How about literature itself? Big-L literature, & the concept of – or just plain old reading? Sometimes it’s hard to draw a line between art and everyday life. How long had I been living with poetry, or with literature, before I realized it?

I remember my enthusiasm at decoding the black scratches that turned into words when my parents picked up books; I remember reading in a circle with my class, each of us sounding out a few lines. Especially I remember being confused when my turn came, because I had read on ahead and didn’t know what page the class was on. The previous line had ended on the word “city,” and I recall looking for that word, but because I was dependent on sounding out the word, I was searching for something that began with an “s” – sitty, perhaps. I must have skipped over “city,” or maybe I thought it referred to a kitty. Words on a page were filled with a strange potential – who knew what they might end up signifying? But I didn’t ponder that notion. My youthful enthusiasm had carried me away, and the vagaries of English spelling and pronunciation were hauling me back to my proper place. Still, I clearly remember being surprised and intrigued – “c” could make an “s” sound! What a world of wonders! This decoding was a complicated job.

Soon I got the hang of it, though, and became a glutton for written words. But while I read almost compulsively, I don’t really remember what I was reading until a much later age – until I get to Finn Family Moomintroll, when I was probably eight or nine. This isn’t the first book I remember – that honour goes to Ezra Jack Keats’ magnificent picture book, The Snowy Day (my daughter likes that one too), which my mother read to me. But among books I read on my own, the various installments in the moominsagas written and illustrated by the Finnish writer Tove Jansson grabbed my young mind in a way other works had not. The adventures of Moomintroll (who has a hippo-ish face, and a round little body) and the other inhabitants of the Moominvalley (& beyond) quickly became addictive. I read as many as I could find, which was quite a few, and I wrote my own Moominish tales. And then the Moominfamily and their circle disappeared. Our family moved to a different city in a different province, my new elementary school’s library was Moomin-less, and I scavenged for other literary sustenance (mainly, from what I recall, Richmal Compton’s “Just William” books, which were even older than the Moomintales and all set in London – also quite intriguing).

Eventually, as an adult, with literary research skills well-honed from graduate studies in English, I found myself wanting to revisit the Moomins, and so tracked down some second-hand copies online (no new ones being immediately available). And when I reread them, I was astonished at the psychologically rich, nuanced (& often quite dark) world Jansson had created. Moominpapa’s extended depression, which prompts him to abandon his family for a year and travel the seas with string-like creatures; the moody, introspective Snufkin, Moomintroll’s best friend; Moomintroll’s discovery of the harshness and hostility of the world in Moominland Midwinter. What had I been ingesting into my malleable young brain?!?

Complex stories, that’s what. Stories with flawed protagonists, ambiguous resolutions, (Mo)ominous and challenging subtexts. Was it Big-L Literature? Damn right it was, although I know it at the time, being unfamiliar with the notion of “literature.” My path to Shakespeare, Hardy, Eliot (George & TS), William Morris, Seamus Heaney, Thom Gunn, Ursula Le Guin, and those countless others whose works have enriched my world – most recently, the Icelandic writer Sjón – was paved with stones hewn in the Moominvalley.

I have since discovered that Tove Jansson, who died in 2001 at the age of 86, also wrote some adult books, including The Summer Book and The True Deceiver, both recently republished by the NYRB press (see Len Epp’s blog, just before mine). They share the same qualities as the moomintales, although they are obviously more explicitly for grown-ups and there are no fantastic Moominish creatures. But the Moomins are what Jansson remains known for, and her creations seem to be everywhere now – I would face no difficulties finding new copies of the books, especially in my neighbourhood, where the Drawn and Quarterly store features a wall-full of Jansson’s oeuvre, especially the Moomin comic strip she created. There is even a Moomin-themed park scheduled to open this year in Japan – following on the MoominWorld theme park and Moomin Museum in (respectively) Naantali and Tampere, Finland.

But even though the Moomins have hit the big time, both on the market and in the Art World, I still feel as if they were my own special discovery. While I no doubt would have found a different route had I not stumbled across Jansson’s creation, I am grateful for having travelled the Moomin road into the world of complex, challenging and engaging storytelling.

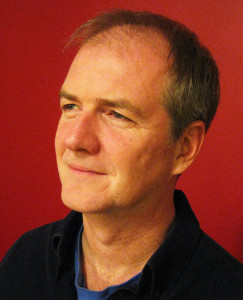

In addition to being poetry coeditor of carte blanche, Patrick McDonagh is a Montreal-based writer & a part-time faculty member in the Department of English at Concordia University where he has taught, among other things, children’s literature. He is the author of Idiocy: A Cultural History, and most of his academic work explores ideas of intellectual difference and disability and how these are represented. He is also on the board of trustees of the International Anthony Burgess Foundation, based in Manchester, UK, and is currently editing an unpublished work by Burgess on the history of London.