When I was seventeen, living in Edmonton, I knew a boy named Mitch who, unlike the rest of us suburban softies, already lived on his own and had to pay his way through life. Mitch was violent, and routinely beat up his friends for perceived transgressions against him. He had a heroic scar on his face from the time he pissed off a drug gang and they went after him with a hatchet.

Mitch was the first to introduce me to Fyodor Dostoevsky. In addition to being extremely violent, Mitch was extremely talented as an artist, and left Edmonton in the late 1990’s to study fine arts at Concordia University in Montreal. But that’s a digression. The year is 1993, I have just graduated from high school, and I’m in Mitch’s tiny studio apartment just off Edmonton’s Whyte Avenue. He shows me a series of illustrations that depict scenes from The Brothers Karamazov. All I can remember now are characters crowded into cramped rooms with very intense looks on their faces, all immaculately rendered in Mitch’s pencil drawings.

I don’t think a lot more about Dostoevsky until four months later. I’m on what the English call a “gap year.” I’m one of the hordes of backpackers that descend on mainland Europe, looking for adventure. I tour around and eventually arrive in Paris. It’s hard to leave Paris. At Aloha Hostel, you can rent a bed in a dormitory for an entire month at a discounted rate. So that’s what I decide to do. I become friends with the hostel’s front-of-desk staffer, an American. We get talking about books. The American, like Mitch, is a huge fan of Dostoevsky. He tells me a remarkable tale.

It goes like this. Dostoevsky and his circle of political agitators in Tsarist Russia were busted for illegally operating a printing press. They were marched into a square and lined up against a wall to be shot. At the very last minute, a message came through from the Tsar: the prisoners weren’t to be shot after all. They were to be sent to Siberia. That was where Dostoevsky spent the next nine years, first as a labourer in a prison camp, and subsequently as a low-ranking military officer.

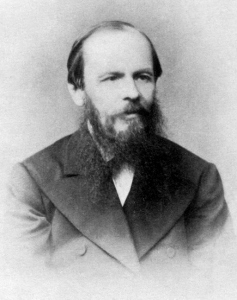

Fyodor Dostoevsky. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

All this astounds me. I desperately want to be a published author, and the story of the sufferings that Dostoevsky endured on his way to literary acclaim makes a lasting impression.

At that time, backpackers would freely exchange books with each other. It wasn’t long before a copy of Crime and Punishment made its way into the hostel. I don’t remember what I traded for it. Maybe The Picture of Dorian Grey?

A few months later, I’d managed to find myself a sublet at the top of a big apartment building on the rue Duguay-Troin, a tiny street that lives in almost perpetual shadow. It’s just around the corner from the Jardin du Luxembourg, where rumour has it, the poverty-stricken Ernest Hemingway used to lure pigeons with bread and then snap their necks, take them home, and cook them.

I immerse myself in the classics. I can’t get enough. I have so much time on my hands, I’ve even got the patience for War and Peace and To the Lighthouse. I work only twice a week, three times at most, babysitting some kids by Bourg-La-Reine and teaching English to a stubborn, chubby boy living somewhere else – I forget now, it’s near some forest. I feel I never have enough money, even though my Dad kindly wires me a couple of hundred dollars every month. My sublet is a studio with a sink in the corner. There is a shared toilet for everyone on the floor. There is no shower.

One day, I discover a cockroach crawling by the skirting board. This, I think to myself with a mixture of pride and self-pity, is what a broke writer must endure!

My copy of Crime and Punishment is still unread. I open it, a little scared. I start to read. There is a long description of a dream in which a horse is flogged by its merciless owner. I can’t believe how visceral and unrelenting the scene is. Not long after, Rasknolnikov, “our hero,” kills an old lady, a pawnbroker, with an axe. I’m hooked. I can’t stop. I’m lying for hours at a time on my thin mattress, until my back starts to seize up and I’m in immense pain. I limp around the streets on my habitual daily scrounging for fresh bread and cheese, feeling quite paranoid of everybody. I return to my garret, which to me seems about the same size as Raskolnikov’s. I eat my cheese and tomato sandwich, leave for the washroom, and when I come back, there’s a cockroach on my plate, eyeing up my meal. The nerve!

I zoom through the cat-and-mouse scenes between Rasknolnikov and Porfiry Petrovich, the investigator on the case of the pawnbroker’s murder. I hate Porfiry. I can’t get over what a motor-mouth he is. He takes gleeful delight in tormenting our hero. I do not want Rasknolnikov to get caught. What’s wrong with me?

An exterminator comes to spray for the cockroaches. The next day, three cockroaches crawl out from the skirting board and die on the floor.

I’m resentful of having to go to work, or having to use the toilet. I’m resentful of anything that takes me away from Crime and Punishment. One day, I go about my habitual business to the bathroom, and when I return, I discover that the door of my room has been blown shut by the wind. What an idiot I am! I left the window open and now look what’s happened!

I am pretty sure that the ledge on the outside of the building, up here on the seventh floor, is big enough to support a human. No problem. I’ll climb out through someone else’s window and tippy-toe around to my own window and climb back inside. But first I need to convince one of my neighbours, none of whom I’ve ever met (everyone ignores everyone in the hallways, it’s the big city way) to let me into his or her room.

One by one, I start knocking at doors. Most people aren’t home. Well, of course. It’s a weekday. Most people have jobs or go to school. Eventually someone answers. It’s a young woman’s voice. I negotiate with her through the door in my still-basic French. She finally lets me in. “It’ll be easy now!” I say. “Look, I live just over there.” The building encircles a small courtyard and you can see my apartment opposite. “Alright,” she says. “Be careful. Don’t fall.”

Out I go onto the narrow ledge, look briefly at the paving stones a hundred metres below. I tiptoe very carefully, holding onto any craggy part of the wall that juts out. The young woman is watching me. She is very beautiful. I imagine that perhaps I look a bit heroic to her.

I re-enter my room, relieved. I did it!

I never have the courage to talk to the young woman again, of course. I finish Crime and Punishment. I am better at books than at life… From that point on, I’ve loved the work of Dostoevsky, and revisit it over and over. For me he is a writer who speaks not just to my head or heart, but also to my soul.

Laurence Miall is a Montreal-based writer who spent his childhood in England before emigrating to Canada at the age of 14. His debut novel, Blind Spot, was published by NeWest Press in the fall of 2014. He has published short fiction and non-fiction with Cosmonauts Avenue, The Edmonton Journal, Art Threat, and other online and print publications, and his stories have been finalists in the Summer Literary Awards contest and the Glimmer Train Short Story Award for New Writers. He is the co-editor of carte blanche.

Laurence Miall is a Montreal-based writer who spent his childhood in England before emigrating to Canada at the age of 14. His debut novel, Blind Spot, was published by NeWest Press in the fall of 2014. He has published short fiction and non-fiction with Cosmonauts Avenue, The Edmonton Journal, Art Threat, and other online and print publications, and his stories have been finalists in the Summer Literary Awards contest and the Glimmer Train Short Story Award for New Writers. He is the co-editor of carte blanche.