By Yilin Wang

“I’m writing a novel in English that’s inspired by wǔxiá fiction.”

As I finished speaking in Mandarin, forty middle school students stared back at me with stunned eyes. It was as if I had suddenly transformed into a xiákè, a wandering warrior, who had stepped out of the pages of a wǔxiá novel and into their classroom in Chóngqìng, China. In reality, I was only a visiting writer and translator, with no martial arts skills or supernatural powers, recently returned to visit the land of my birth.

Gasps and questions continued, becoming louder and louder.

Mrs. Hé shushed her students and turned to me with awe. “Wǔxiá fiction is so rooted in traditional Chinese literature and culture. How can you write wǔxiá in English?”

I smiled and launched into a more detailed explanation. “Legend of Condor Heroes is currently being translated into English. Other wǔxiá novels have been translated too. Some Anglophone writers already draw on wǔxiá traditions.”

Wǔxiá, which I translated as martial arts fantasy, is often considered quintessentially Chinese. The stories feature xiákè, whether a hero or outlaw or someone in between, who journeys through an unknown, violent, and often romanticized jiānghú world. The genre shares similarities with warrior tales from many cultures. But it is full of lyrical names for characters, clans, and martial arts moves that sound awkward and wordy in English translation. On top of this, the genre relies on countless literary, historical, philosophical and religious allusions.

My shoulders sank, overwhelmed. After sharing this, I had no energy to mention the even wider chasms that existed. Many wǔxiá-inspired fantasy novels in English have been written by white authors who had Orientalist obsessions with ancient China, resulting in stereotypes, assumptions, and misunderstanding. Mysterious kung-fu fighting monks. Hidden magic. Exotic foods. Depictions of foreignness, even when all the characters are Chinese.

And beyond that, there was the male gaze. The oldest wǔxiá folktale with a martial arts heroine, “The Sword of the Yue Maiden,” dates all the way back to the Spring and Autumn period (771 to 475 BCE), and it’s followed by many other tales like “Niè Yǐnniáng” and “The Woman in the Carriage.” But these stories were mostly written and continue to be told by straight, cisgender men.

Mrs. Hé interrupted my thoughts. “Are you okay? What’s wrong?”

I quickly pulled myself together, grinning at her and the students. “I’m fine. It’s going to be a long road, but I’m excited.”

When I was eleven, around these students’ age, I immigrated overseas to join my mother in Canada. Alone in a new land and not quite fluent in English, I spent many hours on a forum for Chinese middle schoolers. In cyberspace, we role-played xiákè characters, making up virtual martial arts “clans” with names like Misty Dream Pavilion and Mystical Rose Palace. The fictional clans we formed were a common trope in wǔxiá novels. Later, as I grew older and adjusted to life in Canada, I left the forums, but my love of wǔxiá remained.

No matter the difficulties, I shall persist, for eleven-year-old Yilin, and for those like her.

#

Nearly a month before my visit to Chóngqìng, I boarded a fourteen-hour flight from Vancouver to Hong Kong. I had been counting the days until I’d set out on my quest, a three-month trip to visit historic sites, schools, writers, and scholars related to wǔxiá fiction and martial arts. They formed the real-world counterpart to the fictional jiānghú, literally translated as “rivers and lakes,” a wild landscape through which xiákè roamed. And here I was, crossing land and sea to visit.

Yet, as I sat on the dimly lit plane waiting for take-off, I couldn’t help but sob, already aching from old scars. Wounds that hadn’t yet healed were ripped open again.

A few days beforehand, I had published a statement on my blog titled “Racism in #CanLit: Barriers in Publishing & The Need for Safe Spaces.” My blogpost explained my experience witnessing an old white male bookseller, retired library studies professor, and literary awards organization board member make racist comments against Chinese poets. At a book sale that he had co-organized, he mocked a Chinese poet who had read their work for ten minutes in Mandarin. As a writer, translator, and editor who had once read myself in Mandarin at that same multilingual reading series, and who regularly drew on Chinese literary influences, I felt his words like the stabs of a dagger. At the time, I was the volunteer Poetry Editor at P, an Asian Canadian literary journal. They republished my blogpost soon after I had written it.

The night before my flight, I received an email response to my statement, another attack by W, a white man. I sighed as I re-opened the email and skimmed it, cringing at many sentences:

I am therefore surprised to learn that Canadian Chinese find that they are marginalized or feel “unsafe” at literary events.

You ask others to intervene when they witness racism. […] Why don’t you Ms. Wang?

If you want to earn your proper place you have to personally fight for it. No one will give it to you. Check the history of human rights.

At what point will Canadian Chinese no longer feel marginalized? Perhaps when every other group is marginalized to their dominance.

W’s email referred to me specifically by name, but he had sent it only to the male Asian editor-in-chief at P.

Unlike the legendary xiákè in wǔxiá novels, I had no fighting skills or weaponry to defend myself, only my friends and allies in the community, my martial arts clan in real life and in cyberspace. I wanted nothing more than to believe that the literary magazine P, with its mandate of supporting Asian Canadian writers, would have my back. But P’s editor-in-chief proceeded to forward W’s email to over a dozen people on P’s team, including me—but without reaching out to me first. He didn’t express any words of sympathy, nor any criticism against the email.

Laying down my phone, I took out the box of P’s business cards that I had packed for my trip, as a part of my promise to help P connect with writers overseas. The metal card case was hard and icy, like the steel blade of a knife, with the power to fight, protect, or backstab. My plane shook in mid-air, blown by strong gusts of wind, unstable in the nebulous airspace.

In wǔxiá novels, a jiānghú isn’t only the physical wilderness, but also the space where commoners, underdogs, and marginalized folks live. It can be beautiful, freeing, bloody, or dangerous. I hadn’t yet stepped foot into the real-life counterpart of the fictional jiānghú world, and already, the CanLit world I had left behind was transforming into a shadowy jiānghú I barely recognized. My vision was blurred by tears as my plane landed, bouncing and jostling, its wheels rolling down the misty runway of Hong Kong International Airport.

#

“Please take me to the Hong Kong Heritage Museum,” I said to my taxi driver in English.

“Where?” he asked. He then switched into Cantonese, rambling a long stream of rough sounds that I couldn’t understand, with unfamiliar tones and inflections. “Where’s that?”

It was my first time in Hong Kong, and my first time hailing a taxi here. I was a lost traveler in the jiānghú of Hong Kong’s cityscape, sleepy and jet-lagged, barely able to talk in either of the languages I knew. And whichever language I chose would be political. English, an official language, was the voice of Hong Kong’s former British colonizers. The status of Mandarin in Hong Kong seemed even more complex, historically and continually threatening to displace Cantonese. Suddenly, my private struggles of navigating the politics between two languages—as a translator facing the blank page—became an even more complex, everyday reality.

Using my phone, I pulled up the name and address of my destination in Traditional Chinese. The script was widely used in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and overseas, accessible to both Mandarin and Cantonese speakers.

The driver read it and switched into Mandarin, an accommodation that I was grateful for. “Got it,” he said. “That’s so far. In New Territories.”

He drove through Hong Kong’s busy cityscape, crossing bridges and tunnels, passing occasional views of the misty shoreline and sea. The city was covered by colourful signs written in a mix of Traditional Chinese and English. Although I couldn’t understand Cantonese, I could read nearly everything. Though I had grown up in Mainland China learning Simplified Chinese instead of Traditional Chinese, my appreciation for the older script had increased over the years. Traditional Chinese script preserved traces of etymology and history that were sometimes lost and erased in Simplified Chinese. The hybrid texts in Hong Kong’s cityscape acted as a mirror, reflecting the voices in my bilingual mind and the multilingual city.

The taxi driver continued in Mandarin. “So where are you visiting from? Are you here on vacation?”

“I’m visiting from Canada on a research trip.”

I waited for him to ask the question that I most dreaded, often arising at the slightest hint of an accent when I spoke in English. Where are you really from? I didn’t get the same question in Mainland China, where I could pass as a local by speaking Mandarin. There I often received confused praise for the fluency of my English. After living in four countries, none of them wanted to claim me as their own.

“Some of my friends have been to Canada,” the taxi driver replied. “Welcome to Hong Kong. Have a good visit.”

Glancing up at the taxi’s rear-view mirror, I could see him smiling, an unexpected and friendly guide. He kept driving for more than half an hour. As the taximeter continued to rise, I realized that I hadn’t prepared enough Hong Kong dollars in cash.

“Do you take credit cards? I’m sorry… I just arrived and don’t have enough HKD.”

“We don’t take credit cards in taxis here,” he replied. “Got any yuan?”

“Sorry, no…”

“American dollars?”

I dug out my wallet and counted my bills. “I have some HKD… and Canadian dollars?”

He laughed. “Sure, that’s fine.”

My cheeks reddened as his amused chuckles continued. He took my awkward mix of bills and coins in different currencies, reassuring me again it was fine.

“Thank you,” I said as I stepped outside, flooded by an unfamiliar feeling of acceptance, of home.

#

At the Jin Yong Gallery in Hong Kong Heritage Museum, I stood in front of a colourful display wall, staring up at the multilingual international covers of Jīn Yōng’s novels. As the best-known wǔxiá writer in the Chinese-speaking world, Jīn Yōng spent most of his life in Hong Kong, where he penned fifteen single or multi-volume works of wǔxiá fiction from roughly 1955 to 1970. His works have sold a combined total of over 100 million copies, as well as been translated into English, French, Korean, Japanese, Vietnamese, Thai, Burmese, Malay, and other languages.

In Jīn Yōng’s books, xiákè often travel far in search of rare martial arts manuals, longing for the secret techniques, qì cultivation advice, and cryptic wisdom within those pages. Perhaps, among his manuscripts and artifacts related to his work, I would also unlock key knowledge, details about his literary influences and hints about how wǔxiá can be translated into English.

In his handwritten manuscript “Benefits of Reading,” Jīn Yōng writes that reading was the most important activity in his life aside from breathing, eating, drinking water, and sleeping. Another glass case displayed one of his favourite books, a battered and annotated copy of the multi-volume reference chronicle Zīzhì Tōngjiàn (Comprehensive Mirror for Aid in Government). First published in China in 1084, the chronicle records the official history of sixteen dynasties that spanned nearly 1,400 years. So far, my discoveries matched my understanding of Jīn Yōng’s work, which drew on rich layers of allusions and history.

But, beside the book, I uncovered surprising notes about his influences. Jīn Yōng used to write film reviews under the pen name Lín Huān, suggesting his exposure to a wide number of Chinese and international films. One exhibit panel commented that his works use techniques like cliffhangers and freeze frame, which were borrowed from international films and rarely present in Chinese literature before his time. Jīn Yōng also stated that he found inspiration from Greek myths such as Pygmalion, The Count of Monte Cristo, and Shakespeare’s plays.

Later, at archives in the Hong Kong Public Library and elsewhere, I found essays by wǔxiá scholars who elaborated on these influences. Many of Jīn Yōng’s works explore the same struggles against fate and determinism that are found in Greek and Shakespearean tragedies. Unlike earlier Chinese literature written in an omniscient viewpoint, some parts of The Legend of Condor Heroes unfold like a stage play on a set, with scenes and events happening simultaneously in different rooms of the same building. Fox Volant of the Snowy Mountain, a story told through different perspectives over the course of a single day, also draws on narrative techniques present in One Thousand and One Nights, The Count of Monte Cristo, and the Japanese film Rashomon.

I also discovered that Taiwanese wǔxiá author Gǔ Lóng had similar, wide-ranging influences. In his essay “Regarding Wǔxiá,” Gǔ Lóng acknowledges that his series Meteor, Butterfly, Sword is strongly inspired by the plot and characters of The Godfather. This admission, along with his sparse language, focus on atmospheric descriptions, and depictions of sword fights that resemble the Mexican standoff, lead scholars to speculate that his works have been influenced by Western novels and films. And as I kept tracing the lines of influence, I learned that many Westerns themselves have been inspired by Japanese films like The Seven Samurai.

I had set out on my trip in search of one perfect training manual, but instead discovered dozens. Wǔxiá fiction has more complex roots and influences than I expected. As I attempted to write a novel in English that draws on the genre’s conventions, I was in fact continuing a long tradition, bringing the genre and its hybrid voices back into the Anglophone world.

#

During my travels through the jiānghú of wǔxiá literature, I began and ended each day with emails to and from my colleagues at P magazine. After receiving the insensitive email written by W, I asked folks at P for support and sensitivity. Like found family, the members of a clan fought together and protected each other. But the clan that I once trusted, full of friends and allies, quickly became clouded by a heavy fog, masking shadows, rough edges, and hidden weapons.

One staff member at P replied that she wanted to “thank [W] for being a reader and supporter of Chinese culture.” She even stated that “the point [W] makes about change is correct, we can not be polite and expect things to change with no action.” Her words aligned with W’s email, blaming me for not speaking up and for inaction, overlooking my work in writing a statement, and the emotional labor and the personal risks that I took in speaking out. She offered no critique of the bookseller’s racist remarks, W’s email, or the systemic structures that led to racism. Another editor at P agreed with the suggestion to thank W.

Email exchanges escalated into the writing of a draft response without my input or agreement. An in-person meeting took place in Canada without me, despite my insistence to take part via video call. I was told that meeting minutes were prepared, but the minutes I received held no information about the team’s discussions of W’s email.

Outnumbered and faraway, I was forced to fight for my right to be heard, for the chance to defend my own statement and lived experience instead of having others decide or speak for me. I was stabbed in the back by own clan, betrayed by once-trusted allies. I resigned from my position at P, cutting ties using the invisible sword of my words.

In the end, some members at P cared more for a white man’s voice and white fragility than protecting a woman of color from repeated trauma or actually fighting racism. P was like the famous reputable clans in a wǔxiá novel that spoke of honour and made grand gestures but never followed through on their words.

After my resignation, P’s editor-in-chief retroactively sent me a “Social Media Policy” that I had never before seen or signed. He and a male board member at P’s parent organization escalated the conflict by sending me an “official warning” to remove my social media posts about P’s insensitive handling of the issue, threatening “legal repercussions” and “more action.”

The fights at P and my departure were more isolating than my travels through unfamiliar lands. I deflected their blows, refusing to stay silent, becoming a lone wanderer in the jiānghú of CanLit.

#

My bus made its slow way up the narrow, winding and dangerous path that circled Mt. Wǔdāng. The sacred Daoist mountain had long been immortalized in wǔxiá legends and novels as the home of the Wǔdāng School of Martial Arts. For the first time on my trip, I felt like a xiákè from a novel, scarred and tired after my travels, but also more experienced and resilient.

Before hopping onto the bus, I had finally thrown away the stack of business cards from P, which I’d brought on my trip and then forgotten about. I dumped them into a garbage bin at my hotel near the foot of the mountain; if I’d had matches, I could have burned the cards, in honor of the comparison of CanLit to a dumpster fire. Later on, during my trip, I would continue to discover P’s business cards stashed away in random pockets, notebooks, or bags. The cards clung to me, pests that refused to leave me alone.

My bus pulled to a stop at Prince Hill Scenic Area, home to the mountain’s largest cluster of Daoist buildings. I climbed up the stone steps of the hill, so named because a prince had meditated here for many years, in search of wisdom. The smell of incense filled the air, thick and spicy, yet much more comforting than any fog. I bowed to the temple’s gods, asking for protection and good luck.

When I turned to leave, I met a group in the courtyard outside. The eldest among them, a white-haired man leaning against a crane, turned out to be Shīfù Xiāo Ān’fā, a respected master of the Purple Cloud Sect of Wǔdāng School. He was making his annual trek to the mountain with his four disciples, who hailed from different provinces across China.

“Are you taking on new disciples?” My voice was half-serious and half-joking. I tried to hide my excitement, to make possible rejection easier.

“I’d consider it.” Shīfù Xiāo grinned. He peered at me, his eyes squinted like playful upside-down crescents. “We have lots of yuánfèn meeting on Mt. Wǔdāng.”

Perhaps it was yuánfèn, fateful coincidence, or the temple gods, that made our paths cross. After leaving P, I was encountering another clan—a real martial arts master and his disciples. He offered a different road into the wǔxiá novels I loved, the physical skills and emotional strength that could be used to protect myself and defend others. They had to continue on their journey up the mountain, so Shīfù Xiāo and one of his disciples offered me their contact information for staying in touch.

I watched as they strolled away from Prince Hill, down a snaking path lined by red walls and emerald-green roof tiles. Before they disappeared, the only woman among them turned to wave at me. She was one of the few female martial artists who I had encountered on my trip, a glimpse of who I could become if I followed her path. She seemed happy and well-supported, even as her eyes searched around for others like her.

Our gaze met for a moment, and then, she was gone.

#

Although the xiákè characters in wǔxiá stories vary wildly in their personality and representation, nearly every of one them has to navigate dilemmas. They can only do their best as they are forced to navigate a jiānghú, struggling between free will and responsibilities, friendships and vendettas, forgiveness and hatred.

I never received any apology from the white bookseller or W. In order to respond to the threats of P magazine and protect myself, I had to go through the arduous process of hiring and working with a lawyer, who I found with the help of a dear friend. P’s leadership responded with gaslighting claims that I had misunderstood the threat. They refused to apologize and issued a public, two-faced tweet pretending to support me. I spoke out using the Twitter hashtag #RacismInCanLit, encouraging others to share their stories. Eventually, the hashtag drew the attention of Rahim Ladha, who donated money to create new literary prizes to support marginalized voices, paving the way for change. The outpouring of support from friends and allies left me stunned, grateful, and deeply moved, even as other former friends vanished into the cold, ambivalent fog.

#

Near the end of my trip, a visiting American writer friend and I strolled along the shores of Hángzhōu’s West Lake. It was a romanticized scenic area frequented by many poets. On our walk, I translated for her the legends surrounding Léifēng Pagoda, which towered over the lake and its shores from a nearby hilltop. According to stories, White Snake was a snake spirit who had finally transformed into a human girl after a thousand years of spiritual cultivation. When her true identity was uncovered by humans, she was unjustly imprisoned in Léifēng Pagoda, seen as an outsider. Monstrous, simply for existing.

Lingering in the shadows of the pagoda, I explained to my friend the conventions of classical poetry from the Táng Dynasty and the challenges of translating those verses. Together, we tried to compose poems in English following the same conventions. The poems we wrote were soon forgotten and lost in a notebook, but I tried the same experiment again later, alone and with others.

A few months after returning to Canada, I woke one day to the news that Jīn Yōng had passed away due to old age. Tributes poured out from different parts of the globe. I learned that Jīn Yōng had once received an honorary degree from my own university in Canada, a personal connection that I hadn’t known. Later, I discovered that his granddaughter was a high school classmate of one of my friends, another surprising tie that felt meant to be.

For fans of wǔxiá fiction, Jīn Yōng’s death seemed to mark the end of a golden age, raising concerns about the future of the genre.

To this day, the original and translated editions of Jīn Yōng and Gǔ Lóng’s works remain on my bookshelf at home, still frequently read in my corner of the diaspora. Although difficult to translate and flawed in representing non-cis-men, these books collectively speak to me in a way that very few others do. I have also begun reading my newly-bought copies of wǔxiá novels by Bù Fēiyān and Cāng Yuè, two Millennial women authors from Mainland China; the publishing of their work, along with the general popularity of web novels and alternative online publishing platforms in the Chinese-speaking world, seemed to be slowly making space for more underrepresented wǔxiá writers to be heard. The multi-faceted influences of all these novels, like the multilingual signs in Hong Kong or my poetry experiments at West Lake, offer me and other diaspora writers a roadmap for literary genre-bending, code-switching, and border-crossing. The spirit of xiákè, passed on through manuscripts and encounters with martial artists, have become my guide through the misty jiānghú of CanLit and lands beyond.

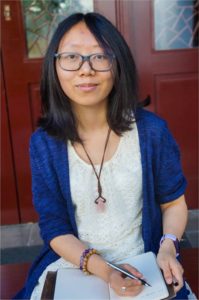

Yilin Wang is a writer, editor, and Chinese-English translator who lives on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples. Her fiction, poetry, and creative nonfiction have appeared in Clarkesworld, The Malahat Review, Grain, Arc Poetry Magazine, CV2, carte blanche, The Toronto Star, The Tyee, Abyss & Apex, and elsewhere. Her writing has been shortlisted for the David TK Wong Fellowship, a finalist for the Far Horizons Award for Short Fiction, and longlisted for the Peter Hinchcliffe Short Fiction Award. Her research trip to HK and Mainline China was made possible by the generous support of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada and the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada’s Asia Connect initiative. Website: www.yilinwang.com.