Top Ten Canadian Key Words and Phrases

The idea behind “keywords” is that people can speak the same language in a formal sense—say, English—and at the same time speak a very different language, one that is bound up with their own individual or group history and interests. Raymond Williams explains the idea well when he describes what it was like for him to travel back to Cambridge from his artillery regiment, in 1945, after an absence of four and a half years:

When we come to say “we just don’t speak the same language” we mean something more general: that we have different immediate values or different kinds of valuation, or that we are aware, often intangibly, of different formations and distributions of energy and interest. In such a case, each group is speaking its native language, but its uses are significantly different, and especially when strong feelings or important ideas are in question.*

In this post I’d like to use the concept of key words and phrases more specifically: what makes them key is that although their meaning is obvious to other members of their own group, other speakers of the same language would interpret the same word or phrase in nearly the opposite, or sometimes exactly the opposite, way. These kinds of “strong” keywords get to the heart of what makes a culture unique; they invoke uncomfortable concepts and commitments of such intense interest that people can sustain in their day-to-day thoughts a severe contradiction between what they know the word or phrase means to everyone else, and the way they choose to use it amongst themselves.

These words and phrases are all around us. Since many people are familiar with American political discourse, I’m going to choose one of their key phrases as an example: “family values.” Now, someone familiar with the English language, but unfamiliar with American culture, might think this refers to something generically having to do with one’s beliefs about, say, ethics and family life, or something. Thus, different people can of course hold different “family values.”

But we all know that what it really means, in an American context, is two things. First, it refers to a particular set of values that are anti-abortion, anti-gay, anti-marijuana legalization—you know what I’m talking about. Second, it is an abusive attempt to exclude all other formulations of family values from the discourse of “family values.”

So, for example, if you support marijuana legalization because you think the damage done to individuals and their families by going to jail is worse than smoking marijuana, you are counterintuitively represented, by “family values”-types, to have “no family values.” This key phrase is so powerful that you actually can’t refer to “family values” in the United States in its literal sense: to do so is always to signal an allegiance to a particular philosophy of family values.

So, with that said, and indeed, with that warning, here’s my list of the top ten Canadian key words and phrases:

1. “Central”

Here’s a map of (most of) Canada. Take a moment to think about which part of the country you would say is central:

Here’s the same map, but with a blob indicating the region that is referred to as “central” Canada in conventional Canadian discourse:

Seriously.

That little red region down there includes our capital city, Ottawa, which sits on a latitude south of Portland, Oregon, along with our biggest cities, Montreal and Toronto, and our most densely populated areas. “Central” Canada is thus well south of the 49th parallel, south of North Dakota, even, and lodged in the bottom right corner of the country, hugging the American border. So much for the “Great White North.”

To understand the “strong feelings and important ideas” behind this key word, all you need to know is that Canada was colonized for the most part from east to west by people whose settlements of primary importance ended up in this area. It was essentially the staging area for the colonization of the country.

Things have obviously changed in Canada over time, demographically, socially, economically, and politically. But there are still those whose interests, whose very sense of what counts as Canadian, are rooted in a historical moment of high colonialism. Thus, the concept of this region’s “centrality” persists.

In this sense, the Canadian use of the word “central” is what I like to call a “desperate anachronism”: the nasal echo of a chinless ghost that lingers on, unaware that it has died, a postcolonial tailbone tarrying stubbornly in place of a power that has already passed.

2. “Sorry”

Sorry, everyone else, but when Canadians apologize to you it’s not an expression of deference. Unlike “eh”, which means to Canadians what it means to everyone else—it’s an invitation to polite disagreement, the opposite of the British “don’t they?” or “aren’t they?”—the Canadian “sorry” means something more like “Ah jeez, I’ve got to deal with this idiot?” (Say it in a Fargo accent to get the full effect.)

When Canadians apologize in the stereotypical way, they are actually engaging in an act of pragmatic magnanimity. It means that they have no respect for either your opinion of the issue at hand, or for your opinion of them. Let me put it in the politest way I can: if you were walking in the jungle and a monkey started chattering and throwing his faeces at you from a tree, no one with a sense of dignity would actually shake his or her fist and shout at the monkey; he or she would just smile at the silly monkey and move on, trying to get on with his or her life. If it means the monkey loses some respect for you, what do you care? After all, really, it’s behaving just like you should expect a monkey to behave, and really, they’re kind of charming in their own, silly way, aren’t they?

Oh, and I’m sorry, my fellow Canadians, but it’s about time they all knew.

3. “Chamber of Sober Second Thought”

If other English speakers were asked to explain the meaning of this quaint phrase, they might think it’s a metaphor for a hangover, or even a colourful description of what your bedroom feels like the morning after a big party, when you discover to your genuine surprise that you are not alone.

But no, it refers to Canada’s Senate, and it does so, purposefully, by invoking the deeply anti-democratic, reactionary rhetoric prevalent in British conservative political pamphlets in the late 1790s and early 1800s. At that time, it was common for those who objected to the recent American and French assaults on class and the monarchy, to use language that characterized the revolutionaries as drunks. This is meant to be a way of reasserting class dominance in two important senses: it implies at once that the lower classes can’t control themselves, and that they can’t think straight. (If the fact that this kind of language could be commonly accepted in Canada surprises you, please note that much of what became “central” Canada itself was set up in 1791 as a bastion for reactionary Loyalists.)

The unwritten part of Canada’s constitution still contains many such anti-democratic feelings. This is why we are saddled with an appointed Senate stuffed with characters who would have been right at home in a Rowlandson caricature, under the pretence that they represent our betters. Never mind that what a seat in the Senate really is, as every honest Canadian has always known, is a late-career reward or sinecure for party hacks and unctuous fundraisers (and can someone please tell me why, almost to a man, the men look like they’re named “Gordon?”); the fact is that, nonetheless, their eminence, once conferred, has been so unassailable, it could be elevated beyond question by nothing more than a quaint phrase.

4. “Storied”

Here’s how the OED defines “storied”:

Celebrated or recorded in history or story.

This is actually a word that, in other countries, is used very rarely, usually to invoke a shared event or person or place from a nation’s history that holds special importance in the nation’s collective sense of itself, especially its own positive achievements and sacrifices.

In Canadian discourse, however, “storied” is used almost exclusively to refer to an ice hockey team called the “Toronto Maple Leafs,” and rather than being used to refer exclusively to the team’s history, calling the team “storied” is in fact an attempt to insist that there is greatness in this team in the present, too.

One could perhaps excuse this effort, on the part of Leafs supporters who have a voice in the Canadian media, to throw their historical weight around, since they have had nothing to brag about since they last made the Stanley Cup finals 47 years ago. But what makes this word so interesting is that it’s really a desperate attempt to wag a finger and make sure all Canadians know that the Leafs ought to matter to all Canadians in some special way, for some special reason (there are five other Canadian professional ice hockey teams, each equally dear to its supporters). And if you’re wondering what that reason is, and whence the desperation, you might want to re-read the concluding sentence from the section on “central,” above.

5. “Buddy”

If a Canadian calls you buddy, best watch your back, guy.

6. “Democracy”

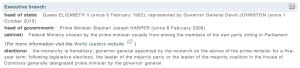

Here’s the section on Canada’s executive branch of government, from the current version of the CIA World Factbook (you can click the image for a clearer view):

It used to say “elections: none,” but you get the picture.

Curiously, in spite of the fact that Canada is a monarchy, Canadians continue to refer to their country as democratic, and to consider themselves to be citizens of a democracy. We are not: we are, rather, subjects of a monarch, who inherits the position.

So when Canadians say that Canada is a “democracy,” they are actually saying it’s a “constitutional monarchy,” which is in fact something very different. And, in any case, the argument that monarchy and democracy are compatible is, in fact, a monarchist argument.

But what really makes “democracy” a strong key word in Canada is what usually happens at this point in the discussion: someone says that the Candian monarchy, and the Queen of Canada herself, is just symbolic, which really means that our form of government does not matter. And it is that fundamental complacency, that final capitulation, that really makes our country something very different from a democracy.

7. “Bilingual”

When my father was a young man, applying for his first government job (he ended up being a career environmental civil servant), and he got to the part that asked whether he was bilingual, he cheerfully answered “Yes.” The reason he did so was simple: in addition to being fluent in his first language—German, the primary language of his multilingual immigrant parents—he was also fluent in English, and so he knew what the word “bilingual” meant.

Here’s the OED again—I’m sure this definition hasn’t changed much in the last 50 years:

As n., one who can speak two languages.

Later he learned he’d made a classic second-generation immigrant’s mistake: “bilingual” didn’t mean what he naively thought it meant, in English; Canadians, real Canadians, understood that it meant something else: one who can speak English and French.

What this use of the word signifies to people who are sensitive to issues of language and race is probably unnecessary to explain. However, I will point out that given the facts concerning demographic trends in Canada, sustaining the unique meaning of this key word will be more and more difficult as time goes on. If you keep watch over just one key word in Canadian culture, make it this one.

8. “International”

This one will probably be the most difficult for me to explain, both to Canadians and to non-Canadians.

In conventional Canadian discourse, the word “international” conveys a very special and complex, and always positive significance. Over here, you can actually refer to a person as “international,” and it is always meant as some kind of compliment, one that comes, I’m not kidding, with slightly widened eyes and a slightly raised chin, and a general sense of everyone present participating in something of special importance. There’s a whiff of it in Canadian expressions of concern about “Canada’s reputation on the international stage,” where it is naively assumed that those who are assessing us are always and inevitably those whose opinion of us is something that merits our concern.

In an important sense, the Canadian use of the word “international” expresses a deep truth about this country: that between it and the rest of the world are three oceans and the United States (which is “American,” not “international,” just to be clear). Thus, the rest of the world—which is actually comprised of real people, living real lives, and pursuing real interests-is reduced to a sort of fashion statement, an opportunity to cut a finer figure at a dinner party, or something.

That’s what makes “international” a strong key word in Canada: its use is restricted entirely to parochial and internal Canadian fellow-signalling. That’s why there’s no serious discussion of foreign policy in Canada, and why we haven’t had one in, like, forever: how can we, when we have reduced the rest of the world to some kind of high school cafeteria where what is most at stake is our own “reputation,” by which we really mean, our sense of ourselves?

9. “Oil-rich”

Surely some cultural theorist somewhere has done an extensive study drawing out the obvious fact that “oil-rich” is a bigoted and usually racist term. It’s been a long time since I’ve read Edward Said’s amazing Orientalism, but I suspect there’s something in there about Westerners invoking the racist caricature of the fat, lazy, “oil-rich” pasha as a way of saying, “those people neither properly earned, nor do they properly deserve, their wealth.” Adopting this attitude offered the colonialist two benefits, in relation to his “oil-rich” targets: first, of course, it meant that it was ok for him to take their wealth away, because they didn’t really earn it in the first place; and second, it buttressed his sense that, deep down, those people really ought to be poor, naturally, and it really is just restoring the natural order, to take them down off their high horse.

In Canadian discourse, some time ago it became conventional to refer to the shifting inhabitants of the province of Alberta as “oil-rich.” Now, a casual observer, or an apologist, might claim this is meant to invoke an environmentalist criticism of the material conditions that dominate the economy of Alberta. Bracketing the fact anyone making that claim has to argue why people don’t just say something like “environmentally destructive Alberta,” or something to that effect, I’d like to point out that the big environmental problem with the oil sands is not the oil per se, but precisely the fact that extracting them is such a labour-intensive process. This is not just true; it is notoriously true.

In other words, what has driven economic growth in Alberta, and made so many working Albertans rich compared to their less-well-paid Canadian brethren, is that oil sands extraction is actually a massive industrial manufacturing and mining operation. And just like all industrial manufacturing and mining operations, it’s dirty, carbon-intensive, and bad for the environment.

So, behind the Canadian taunt that Alberta is “oil-rich” is the repression of a basic fact about the entire Canadian economy: that it is and always has been primarily based on the extraction and sale of resources, and on a heavily polluting industrial manufacturing effort that feeds the maw not just of Canadian, but also of American, consumption. Like the colonialist’s “oil-rich” taunt, this one too is a form of projection.

10. “Opening Up the Constitution”

Non-Canadians should be forgiven for thinking this is an optimistic phrase, invoking the possibility that the Canadian constitution could be opened up and changed. To the contrary, to talk about “opening up the constitution” is more like invoking the scene at the end of Raiders of the Lost Ark, when everyone who actually looks inside the thing gets killed by some blue lightning if they’re lucky, and gets their face melted off if they’re not.

The short explanation for this is, the boomers failed to change the constitution after a couple of tries in the 80s, so now we can never change it. Which in a very important sense means, at least on a symbolic level (ahem), that Canadians are essentially incapable of real change: we are so constituted, such that there is nothing we can do.

Sorry.

* Raymond Williams, Keywords (Revised Edition). Oxford University Press: New York, New York, 1983.

Len Epp wrote his DPhil in English on significance of ʽclarityʼ and ʽobscurityʼ in political and literary writing in the Romantic period in Britain. He is serially publishing a novel satirizing Canadian identity discourse and working on a pamphlet on contemporary political rhetoric in the United States. He is also a contributing editor of carte blanche. You can reach him on Twitter @lenepp.

Len Epp wrote his DPhil in English on significance of ʽclarityʼ and ʽobscurityʼ in political and literary writing in the Romantic period in Britain. He is serially publishing a novel satirizing Canadian identity discourse and working on a pamphlet on contemporary political rhetoric in the United States. He is also a contributing editor of carte blanche. You can reach him on Twitter @lenepp.