This interview is part of a series of conversations between exceptional young writers across genres that will be posted on the carte blanche blog over the following months.

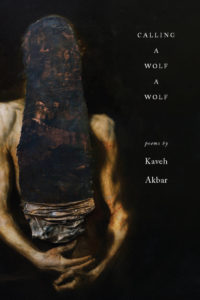

On the way to a reading, Kaveh Akbar talked to Tess Liem about his debut full-length collection of poetry, Calling a Wolf a Wolf (Alice James Books 2017). Among other things, the two discuss the addiction recovery narrative, writing in proximity to violence, and how to allow silence into a poem.

TESS LIEM:

Let’s start where Calling A Wolf A Wolf starts: with faith, the opening poem, “Soot,” and its opening line, “God comes to earth disguised as rust.” You wrote about your relationship to faith and faith to poetry in How I Found Poetry in Childhood Prayer (LitHub), but I was wondering if you would talk a little bit more about the act of praying as a gesture or an action, the verb part of faith, so to speak.

KAVEH AKBAR:

The book is an addiction recovery narrative and for me a big part of my active addiction, a big part of what I found to be my experience, after the fact, was finding that I had done all this harm to myself and to the people that cared about me, but also to my cosmological, psychological station. As someone who grew up Muslim, but not wildly devoutly Muslim–we weren’t a super religious family–it was there, but it wasn’t. I think a lot of the times people expect when you say that you were brought up Muslim, they think that you just came out of the womb with a full beard and holding a Qu’ran, but like Christianity in America, there’s a spectrum. There’s people who call themselves Christian and never go to church. There’s people who call themselves Christian and only go to church on Easter, you know what I mean? It’s a whole spectrum so it was there the whole time I was growing up. It was important but it wasn’t something where it was being closely monitored by anyone, least of all myself. And in the process of recovery a huge part was and is a process of repairing what I damaged in the active addiction. And part of that process of repair was and is the work of repairing my spiritual self, the damages that I did to my spiritual self. And in that process of repairing, a whole new relationship to faith has blossomed and it’s complicated and it’s difficult and I don’t have any concrete answers about it but the poems are where I go to work that out and I think you very much see that process play out in Calling a Wolf a Wolf.

The language of prayer, the rhetoric of prayer is endlessly fascinating and endlessly potent to me because it’s been part of our human language across cultures and nationalities since the dawn of man very literally. And the yearning for prayer is the yearning for something bigger, and so it’s really potent to try to mine that rhetoric in poetry because there’s something lizard-brain about it. Something that’s hardwired into us.

TL:

Yeah and one of the effects, for me, of your engagement with that rhetoric or prayer was that any instance of speaking or naming or calling became a kind of act of faith.

And there’s a couplet in “Do You Speak Persian?” that I thought about the whole time I read Calling a Wolf a Wolf: “Is there a vocabulary for this? / one to make dailiness amplify and not diminish wonder?” This action of amplifying wonder is in the simile’s you use, the way your poems look on the page, the way in which you put together yourself as a subject, and in the closeness of addiction, recovery and faith.

KA:

It’s something I think a lot about, too. I think about how–I was just talking about this with my friend Thora about how wonder is at the heart of all great poetry, and that there is a way in which the world sometimes, when we are oriented a certain way, can conspire to dull our appreciation toward it, to dull our capacity for wonder, and can dull our permeability to wonder. And particularly in this moment in history in America, 2017, when black men are being murdered in the streets and the earth is very aggressively warning us about what we’re doing to it and we’re living in the long shadow of a fascistic regime, there’s a kind of vast conspiracy against our capacity to wonder. And so the work of wonder which seems to me to be essential work for any practicing poet becomes that much more difficult. It’s not a passive process to wonder. And yeah I think that “Do You Speak Persian” is beginning to broach that idea. That moment in that poem especially.

TL:

And this idea is returned to over and over. Later, in the last section of the book, in “My Kingdom for a Murmur of Fanfare” you write, “It’s common to live properly, to pretend / you don’t feel heat or grief…” and there it seems that living without wonder is a kind of numbness. Then you write, “It is comfortable to be alive this way, // especially now, but it makes you so vulnerable to shock–” there is this sense that if you’re not paying attention, if things aren’t wondrous then of course you’ll be shocked about the state of the world in 2017. This is something that makes Calling a Wolf a Wolf feel very urgent.

KA:

I appreciate you reading it so well and that is a great ambition of the book. To feel contemporary to the moment and to be useful in that way. It’s interesting, too, because “Do you speak Persian?” the poem from which you pulled the first line that you mentioned is maybe the oldest poem in the book and the poem from which you’re pulling the other language from, “My Kingdom for a Murmur of Fanfare,” that might be the newest poem in the book so I think you’ve struck upon something really important, which really is a kind of through line.

TL:

One of the other ways I was thinking about this book, and I picked up on this word from your interview with Layli Long Soldier on Divedapper, is the idea of proximity. When we’re talking about wonder, proximity becomes very important. There’s “Supplication with Rabbit Skull and Bouquet,” for example, and many others where things that are sort of opposed or opposite are brought so closely together that their opposition is either undermined, or rather, just closely examined.

KA:

So much of the way that I conceived the book is based around this cosmic pull of the poem, which is to say there is a core, a nucleus. There’s a nucleus and that is the content or the subject or whatever you want to call it and then the poem just kind of orbits that. Instead of thinking about the poem that passes through the content or moves in a linear way through a path of content, I think of a lot of my poems as electroning around a nucleus of content. That is to say that in a poem like the title poem, “Calling a wolf a wolf,” [the nucleus] is “inpatient,” and it’s a story about being in a hospital unit. But it’s comprised of phrases that are all separated by medial caesuras so there’s a kind of proximity in the language and there is an accumulative effect to reading all of these phrases. There is a kind of narrative that forms but it’s not linear, it’s orbital. Does that make sense?

TL:

Yeah! I like orbital as a concept. And, with the medial caesuras, there’s also this wonderful line in “Unburnable the cold is flooding our lives,” near the end,

“almost warm a good harm the addictions.” The effect of that–I had been thinking of it like an equation because of the way that it balances with the next line: “…the addictions / that were killing me fastest were the ones that I loved best.” These spaces are about silence, but a side question is how do you read them?

KA:

I read them as breaths. I think that hopefully on the page they read as breaths or pauses that are a little bit softer than the pause that a period or a comma gives. I hope that the edges are little bit more round. I think that that allows the silence to enter the poem. Something that’s really important to me in both reading the poems and composing them is thinking about how to amplify certain silences, too. I study Jean Valentine very closely. I think that she’s the greatest living poet of silence. I’ve said this before but I’ll keep saying it because I want everyone to read her. I study her to try to figure out how to shape the silence in the poem, using the negative space of language, if that makes sense, like if you imagine one of those pictures of a vase where you can only see the vase in the negative space in the darkness around it. You have language being that darkness and silence being the vase. I want to think about how to sculpt silence using language.

TL: There’s also another poem that I was thinking about a lot in terms of silence, which is “Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and House Fly.” This along with a painting that I think about a lot called Death of Marat.

There’s also another poem that I was thinking about a lot in terms of silence, which is “Portrait of the Alcoholic with Home Invader and House Fly.” This along with a painting that I think about a lot called Death of Marat.

KA:

Oh yeah! And he’s still clutching that final sheet, right?

TL:

Yeah exactly and–

KA:

Which is how any true writer wants to go out–

TL:

Yeah! This image was evoked for me because there is this kind of silence achieved in that poem where something violent has just happened but we’re encountering the moment after, which is such a heavy kind of silence.

KA:

Yeah I love that. Both involve a kind of–well I don’t want to put too fine a point on it–but I love thinking about that relationship.

TL:

This brings me to the idea of proximity to violence and I wanted to ask you about the poem “Heritage.” This is a response to, or an orbiting around, a person and an event and it has this closeness to violence. I wonder if you would talk a bit about writing in response to violence, either just in that poem, or in general.

KA:

It’s difficult. It’s difficult because there’s a power difference between me and Reyhaneh Jabbari who the poem is about. She is someone who has been violently–had her autonomy violently taken away so in my writing about it–you know, I’m a man living in America who is not subject to–I mean, what she was made to endure is literally inconceivable to me. I have no experiential reference for it. So it’s dangerous and I still have complicated feelings about that poem for these reasons. There are many drafts of that poem that were complete failures. I’ve written about this but there are drafts of that poem that completely get it wrong and completely re-inscribe the violence that was levied upon her. I think that the draft that I eventually landed upon is as–it’s as close as I feel I could come to examining the ways in which I was and am complicit in the kind of culture that has allowed what happened to Reyhaneh to happen. It’s as close as I could come to that without also toeing the line of trying to, you know, hang a banner, around my neck saying “I’m one of the good guys look at me” self-flagellating myself. Because I’m not interested in the kind of poem that says “here’s me performing my contrition. Forgive me.” I would never want to write that poem and I have written drafts of poems that were that. It’s a very very delicate poem, one that I’m glad to have had the experience of having written, but one that I’m still very vexed by. I think about Reyhaneh, Reyhaneh’s story, all the time still. It really haunts me. To this day. From the first day that I read about it, I kind of knew that it would, I knew that it wasn’t going to leave me any time soon. But to this day it really still does linger.

TL:

Because of that poem I re-read the translation of the message she left her mother.

KA:

The letter, yeah, isn’t that the most haunting text you’ve ever read?

TL:

It is–and to me, that’s one thing the poem is doing: bearing witness to that text and Reyaneh, bringing attention back to her. And, you’re right, it’s difficult to think through the ways in which poetry interacts with or responds to these things in the world that haunt us and that we need to deal with.

KA:

Absolutely, and I think there is value too just in the fact that you and I are saying her name to each other. Like we are two people living in America [and Canada] and we’re saying Reyhaneh Jabbari’s name out loud to each other years after she was murdered. There’s something powerful about that, too, just giving breath to her voice. That’s something that poems can do.

Kaveh Akbar’s poems appear recently or soon in The New Yorker, Poetry, The New York Times, The Nation, Tin House, The Guardian, Ploughshares, FIELD, Georgia Review, Guernica, Boston Review, and elsewhere. He founded and edits Divedapper, a home for dialogues with the most vital voices in contemporary poetry. He was the recipient of a 2016 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation, a Pushcart Prize, and the Lucille Medwick Memorial Award from the Poetry Society of America. Kaveh was born in Tehran, Iran, and currently lives and teaches in Florida. Calling a Wolf a Wolf is available from Alice James Books and Penguin.

Kaveh Akbar’s poems appear recently or soon in The New Yorker, Poetry, The New York Times, The Nation, Tin House, The Guardian, Ploughshares, FIELD, Georgia Review, Guernica, Boston Review, and elsewhere. He founded and edits Divedapper, a home for dialogues with the most vital voices in contemporary poetry. He was the recipient of a 2016 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation, a Pushcart Prize, and the Lucille Medwick Memorial Award from the Poetry Society of America. Kaveh was born in Tehran, Iran, and currently lives and teaches in Florida. Calling a Wolf a Wolf is available from Alice James Books and Penguin.

Tess Liem’s debut full-length collection of poetry will be out from Coach House in fall 2018. Her chapbook, Tell everybody I say hi, is available from Anstruther. Her writings appear on Plenitude, The Puritan & The Town Crier, the Metatron Omega Blog, in Room Magazine, The Walrus, Vallum and elsewhere.

Tess Liem’s debut full-length collection of poetry will be out from Coach House in fall 2018. Her chapbook, Tell everybody I say hi, is available from Anstruther. Her writings appear on Plenitude, The Puritan & The Town Crier, the Metatron Omega Blog, in Room Magazine, The Walrus, Vallum and elsewhere.