This interview is part of a series of conversations between exceptional writers debuting across genres that have been posted on the carte blanche blog over the past months.

JENNY FERGUSON:

In your bio on twitter, you use the hashtag #UnapologeticallyMuslim. I see this as a radical (in the best sense of the word) and important statement to make. What does it mean to be Unapologetically Muslim in 2018? It is something personal? Does the hashtag define your brand as a Young Adult author? Or is it something else entirely?

S. K. ALI:

For as long as I can remember, even as a very young child, to identify as a Muslim was to proclaim something problematic. I won’t get into the whys behind this—that would take an essay, perhaps a dissertation, and many others have already done this well—but when you find yourself in a position of constantly articulating the humanity inherent in your identity, at some point, points plural, something snaps and you say, enough, I am who I am and that’s it. It’s happened to me several times, this throwing up of my hands to say I’m Muslim and I’m not going to give you any more than that; first in my teen years, then as a woman in her early twenties, mid-thirties and now, as a woman in her forties, once again. The fight ebbs and flows and I hope this phase of just being here in this space, fiercely okay with who I am as a Muslim woman, lasts and I don’t lapse into contortions to make my Muslimness palatable as I’ve done before in order to be “accepted” at some level.

The other part to declaring myself unapologetically Muslim connects to my identity as an author. As a writer, I’m committed to writing authentically not because it’s “trendy” to be an #ownvoices author (gosh, I hate that so much—this concept some people have about diversity in literature being the latest trend), but because I see good art as stemming from raw knowledge and unfiltered experiences. I’m committed to working at being a good artist. This means sometimes diving into things that communities under scrutiny, marginalized communities, may not want to necessarily talk about. Like issues that I’m personally interested in such as misogyny, racism and sexual assault. I want to unpack these issues because in being unapologetically Muslim I recognize that I’m unapologetically human.

My Muslim community is made up of human beings and so we grapple with the ills that all communities do. It’s time to say it’s okay, even though we are under the magnifying glass for almost everything we do, even though we get treated unfairly, negatively, in mass media, even though Islamophobia intensifies everything connected to us, we’re not ashamed to say we’re just as human as everyone else. And if we look at difficult issues from a place of care, despite being unfairly targeted, ultimately, we are the better for it.

JF:

We don’t talk about Young Adult books much here at carte blanche. Why should anyone interested in literature and contemporary culture care about novels meant for teens? What’s happening in the YA world right now that you see as important to all readers?

SKA:

The YA world is an exciting space! Wherever young people congregate is where you can witness change truly happening. A shift is happening in publishing because of young people saying they want to see a shake-up. A whole movement is underway, begun a few years ago, to change the way the publishing industry perceives narratives differing from the ones that made “traditional” sense.

JF:

Are you talking about We Need Diverse Books (founded by writers Ellen Oh and Lamar Giles)?

SKA:

Yes. As well as the #ownvoices movement and other such conversations taking place, mainly on social media

This is a seismic shift in understanding that’s (slowly) occurring: an awareness that stories featuring diverse characters are desperately needed and the best people to tell these stories are those who know them the best: authors of those diverse backgrounds.

When I think back to the narratives I read growing up that included people of my background as a Muslim, as someone of Asian background, as a child of immigrants, I’m astounded at how wrong they got things. Because every one of them was written by someone outside these identities and so featured content awash with stereotypes and misrepresentations and something I call ill-representation—an active attempt to make certain communities look bad due to prejudice and implicit bias.

JF:

Oh my stars, yes. Every Indigenous reader or reader of colour or reader from a marginalized religion or other marginalized community is nodding along with you here. We talk about bad representation a lot over on twitter, but ill-representation hits the note so much harder.

SKA:

One day I’d like to write about the effects this had on my young, burgeoning feminist self, to read the depictions of Indian, African and Arab men by colonial British writers and contemporary feminists, who, though they had enough misogyny in their own backyard to tend to, fixated on the evilness of nonwhite patriarchies.

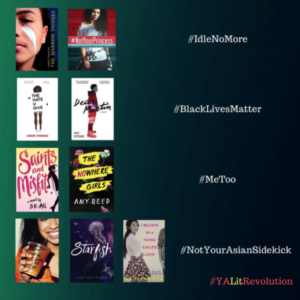

But now, mainly through the activism and efforts of the YA community of readers and authors, there’s a call to clip at this and prune inauthentic, hurtful narratives. It’s ongoing and still very much a work-in-progress but many of the breakout titles of 2017 show a positive change. I made a graphic to illustrate how YA is a LIT space in the literary landscape.

JF:

Anyone who wants to dig into YA, just so you know, this graphic includes some of my absolute favourite reads of 2017, YA or not. Cherie Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves was my last read of 2017 and I’m still utterly speechless. Dimaline’s book filled a little piece of me I didn’t know was missing. That’s powerful. That’s what good representation does.

I’d like to keep talking about representation and this entity called Canadian literature. At carte blanche we’ve talked about #CanLit before in our #WhoNeedsCanLit Series featuring poet Gwen Benaway, critic Alex Good, and fiction writer Mehdi M. Kashani, but I’m not done thinking about what it means to be a writer in Canada. Especially for writers who come from Indigenous or marginalized communities and what it means to have diverse content in the Canadian literary marketplace. I really wanted your debut, Saints and Misfits, to be set in Canada. Flying somewhere between upstate NY and Minneapolis, ugly crying and cheering for these teenaged Muslim girls I was hoping against hope that they were, say, Torontonians. Spoiler alert, they aren’t.

At one point, the mention of a sticky, yummy butter tart really got my hopes up. Butter tarts are quintessentially Canadian. Did you sneak that in as a nod to Canada? And why can’t YA novels be set here? Is this something you’re warned away from as a writer? Or was this a deliberate choice of yours, setting Janna’s story in the U.S.?

SKA:

In Arabic, there’s a tidy little word that’s perfect to open this answer: ummah. Ummah means community, and it can be used to refer to many kinds of communities, but it’s mainly used to signify a group with common beliefs. A Muslim ummah is seen as global—comprised of the approximately two billion people who call themselves Muslims. But there are local ummahs too. And my local ummah growing up was truly North American. The friends I made across the border, at the summer and winter camps I went to each year, at biannual Muslim conferences, were as important as my friends at the mosque I attended on the weekends here in Toronto.

I wanted Saints and Misfits to reflect this experience of continental-belonging. I wanted my readership to include my North American ummah as well as a broader range of readers, beyond Canada. So it made sense to situate my story in the Midwest, kind of in the middle of the continent.

There’s a second aspect to this choice that I’m wary of discussing because I know it will awaken criticism. But I hope we’re at a point where we can understand that true change comes from honestly looking at where we need to grow. So, here goes: though multiculturalism is considered intrinsic to Canada’s character and though the theoretical understanding of this has nurtured me and given me a sense of security to write boldly as a Muslim woman, I still see a long way for us to go toward changing general Canadian readers’ receptions of diverse books, authored by diverse writers.

JF:

I’m agreeing so hard my neck hurts from nodding.

SKA:

When it came time to query literary agents, I generally had a sense that Saints and Misfits would be received well by readers beyond Canada’s borders.

Perhaps this has to do with the fact that a lot of the fight for diverse content comes from U.S. readers and writers; maybe it’s because issues of race and prejudice are more in the open, more in conflict and more debated south of our border. I think our false sense of confidence in this area—that we Canadians are authentically open to diversity! we’re a mosaic not a melting pot!—hinders us from seeing the real picture: racism is alive here too, dangerously masked in politeness. How can we forget it was in Canada, in Québec, that a brazen mosque shooting taking the lives of innocent worshippers happened?

Muslim voices absolutely need to stake a louder claim in the mosaic of our #CanLit literary tradition. Among the first questions I get asked on panels I’ve been on in Canada has been, Why did you set your story in the U.S.? Why not Canada? and I know behind these questions is the hope that I value my Canadianness as a writer. Yes, I do value it. But I also want a wide readership to connect with this #metoo narrative that many—Muslim and not, Canadian and not—have experienced.

I will add here that the second novel I’ve completed, a dual POV one, has a Canadian main character who loves her Tim Hortons! (Dare I say that’s way more in-your-face Canadiana than butter tarts? No, I dare not.)

JF:

I’ll let the Tim Hortons vs. butter tarts debate fall silent so we can move on. Safely.

Religion’s a difficult topic to broach, especially when we’re talking about non-Christian religions like Islam or Judaism, or Christian religions many Christians don’t acknowledge as such, like Mormonism or the Seventh Day Adventists.

Until Simon and Schuster created Salaam Reads in 2016, I don’t think I’d ever read a novel with a Muslim protagonist written by a Muslim writer. I admired what you did so well: open up the doors and invite readers inside Janna’s life. Her uncle, the local Imam, is equal parts charming and insightful. Janna’s parents are complicated, yet full of love for their family. Her brother is religious and wants to get married young, but he’s also a philosophy major. Then we meet Janna’s sort-of friend Sausun, the Niqabi Ninjas, and Saint Sarah. (I’m not even going to talk about the Monster here. I don’t want to.)

You’ve created such a rich world—one where you can’t divorce being Muslim from your characters lives and have your characters still remain fully human. That is, this isn’t a surface thing; it’s not just added on. Being Muslim is part of the air your characters breathe—and as a reader it’s so refreshing. Some writers think they can’t write about their religion, that it will close the market off to them. And worse, that it will marginalize them further. What’s at stake when you include religion and religious themes in a book? Is this #ownvoices movement a place for the rest of us to find our place in the market?

SKA:

Because Islam has daily and weekly devotional and congregational requirements, significant months/days of the year, as well as dietary and behavioral prescriptions (such as cleanliness rites), religion is very much a part of life for many Muslims. We fold it into everyday activities in quite a seamless way. Yet non-Muslims don’t generally get to see what this looks like in popular culture as most media depictions tend to center violent, oppressive or oppressed Muslims. If there’s a positive portrayal, it’s often Muslims who don’t “overtly” practice the faith.

With Janna, I wrote some of the regular Muslim life I see around me but that doesn’t often make it into pages or onto screens. It felt like I was writing to fill a huge void—like I had to write so very much to fill this gap in Muslim representation.

When we went on submission with the manuscript, I knew I had to work with Zareen Jaffery at Salaam Reads because she told me she loved how unapologetically Muslim Saints and Misfits was. She appreciated the way the narrative wasn’t written expressively to cater to a non-Muslim readership and yet was still accessible to a wider audience. In speaking with her, I just knew the “Muslimness” in my book would be preserved. And it was—at no point did I feel like I had to compromise the integrity of the narrative.

My experience tells me that for the #ownvoices movement to really gain ground, we need to ensure that there’s diverse representation at the higher tiers of the publishing industry, in addition to the clearly committed allies who are already there (like Justin Chanda, the publisher of Salaam Reads). I’m hopeful that organized efforts such as PoC in Pub (founded by Patrice Caldwell a writer and an Associate Editor at Disney-Hyperion) will contribute to making this a reality.

Another hopeful thing: readers from a wide variety of backgrounds have embraced the Muslimness of Saints and Misfits and have commented on how this aspect of the book was so refreshing to see. I think people are ready for narratives that smash both stereotypes and the status quo and this is ultimately hopeful for a wider variety of diverse experiences, including the religious, to be explored in fiction. Hopeful and exciting!

JF:

I asked writers to chime in if they had questions for you and chime in they did. It was hard to only pick a few questions to share with you. London Shah (who recently sold her own YA novel featuring a Muslim protagonist to Disney-Hyperion—yay London!) and Fatin Marini had questions along the same line, so I’ll present them to you here, together.

LS:

With regards to the premise, have you encountered any protest from the Muslim community since your novel’s release?

SKA:

No, on the contrary, I’ve been pleasantly surprised with the embrace it has received on the whole. Though, to be honest, I’ve become convinced that had my debut novel had a “lighter” issue at its heart, there would have been more of a celebratory reception of the book in the Muslim community. Right now, I would describe the support it has received as sporadic but strong. And this has helped me to realize the need for joyous stories featuring Muslim characters (and really, light stories featuring characters from all marginalized communities). I know for the Muslim community, this may have to do with bad representation fatigue—just being tired of the scrutiny yet again after years of ill-representation. Hence, my second novel has been a challenge I’ve taken up: can I write a fun, joyous book featuring Muslim characters? I hope the answer is yes!

FM:

What made you want to tackle sexual assault in your novel? Were you worried about how it would be received? In light of #metoo what are your thoughts on where Saints and Misfits fits into the conversation?

SKA:

I’ve been concerned about women’s issues for as long as I can remember, even as a child, and this meant I awoke early to the realities of the many difficulties women all around the world grapple with. It also helped me see how extensive—geographically and historically—misogyny is. No community is immune and so no community is immune to the trauma and injustice of sexual assault. None. I wanted to tackle this issue because I felt strong enough to do so candidly, from an intersectional space. And that’s where Saints and Misfits fits into the #metoo conversation: it provides a much-needed intersectional lens on sexual assault for teens—and adults.

JF:

Congratulations are in order! Saints and Misfits was long-listed for Canada Reads 2018 alongside some other amazing books—including Cherie Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves. As we close our conversation, I’d like to say thanks and give you the last word. What’s been your biggest insight or revelation since your debut was released?

SKA:

One of my biggest insights has been this: that one book can connect with readers for so many different reasons. Some of my readers adored Janna’s relationship with the elderly Mr. Ram. Some thought the romance-lite between Janna and another character I won’t name in order to not spoil things was beautiful. Some were giddy about the sibling relationship—they were so happy that it was authentically conveyed in all its greatness and terribleness. Of course, many were happy to see Muslims represented with nuance. And still others loved the nitty-gritty details of surviving high school because it was so real.

I’m so heartened by this realization. That we writers can write one story and diverse souls will connect with many aspects of it. I mean, I always understood this theoretically, as one learns when studying literary theory in university, but, until my book got published, I never understood the freedom this gives an author.

It, the book you write, truly isn’t yours after it’s published. And I just love that so much, releasing a book from my heart to any of the unique hearts open to it out there. This makes me feel confident to write with unbridled breadth and nuance, hopeful that someone somewhere will find a snug spot to connect with, within the narrative I’ve authored. How wonderful!

S. K. Ali is a teacher and the author of Saints and Misfits, an Entertainment Weekly Best YA Book of 2017and a finalist for the American Library Association’s 2018 William C. Morris award for best debut teen fiction. Her novel has been hailed as groundbreaking in its depiction of a Muslim-American teen’s life. Saints and Misfits has also been long-listed for Canada Reads 2018. Keenly interested in a variety of genres and literary forms, S. K. Ali is currently working on books that reflect this love. She has a degree in Creative Writing and lives in Toronto with her family and a vocal cat named Yeti. She can be found on twitter @sajidahwrites.

S. K. Ali is a teacher and the author of Saints and Misfits, an Entertainment Weekly Best YA Book of 2017and a finalist for the American Library Association’s 2018 William C. Morris award for best debut teen fiction. Her novel has been hailed as groundbreaking in its depiction of a Muslim-American teen’s life. Saints and Misfits has also been long-listed for Canada Reads 2018. Keenly interested in a variety of genres and literary forms, S. K. Ali is currently working on books that reflect this love. She has a degree in Creative Writing and lives in Toronto with her family and a vocal cat named Yeti. She can be found on twitter @sajidahwrites.

Jenny Ferguson is Métis, an activist, a feminist, an auntie, and an accomplice with a PhD. She believes writing and teaching are political acts. BORDER MARKERS, her collection of linked flash fiction narratives, is available from NeWest Press. She lives in Haudenosaunee Territory, where she teaches at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. You can find her on twitter @jennyleeSD.