KdP: I kept waiting for the right time, the right amount of time and concentration to read Rag Cosmology; I had enthusiastically anticipated your book and didn’t want it to be over too soon; it seemed apt, in the end, when the perfect time and location offered itself during a camping trip in Parc des Grands Jardins in northern Quebec over the summer—“this brown day / hosted by beauty.”

Your debut collection is unmistakably ecologically conscious, grieving the damages that have been done to our planet, but also foregrounding organic beauty; connectivity between landscapes and humanity is a dominant theme throughout this book. The ambience of oneness, growth and mutual responsibility that you create adds an almost mystical quality to the book. Does this appeal to unity or shared intelligence stem from an ideological framework or intuitive generosity? I wonder whether you could speak to the process of writing radical empathy when it comes to the environment?

Shared intelligence is a beautiful way to put it. The earth is the ultimate polymath, and our bodies too for that matter. And by intelligence I mean the way systems self-organize to live by ingenious methods. Ourselves included, even as we’re actively dismantling our own ecological framework, and nearly everything else’s as well. That’s the disjuncture I’m working within.

My sense of ecological embeddedness and intelligence stems from an intuitive as well as ideological excursions that are ongoing. I’ve explored many frameworks—ecopoetics, ecopsychology, eco theory, Buddhism—I don’t even know what to call it all—trying to think within this disjunct between loving the world and trashing it. And by the world, I mean us, and by us I mean the relationships that we are.

Radical empathy, when it comes to thinking about environment, for me is about coming into relation with the day and its more-than-human community, which is already the case, even if you don’t notice. So, noticing. A big part of my process is just noticing. One of my favourite practices is to go for a walk and look for performances. Everything performs for you—the dogs, the trees, the people, the garbage—it’s better than the best theatre, because everything is performing itself so brilliantly, all the time, but mostly you miss it (unless you’re on mushrooms or something). And it can be kind of overwhelming too, because after just a block, there’s so much information. So sometimes I apply filters- instead of trying to take in everything, I go for a sound walk, paying attention to the sonic landscape, or just to colours, or squirrels. I don’t know how radical this empathy is, but it brings me into relation with who’s around me.

In a more sustained way, I also have a practice of working with trees, where I spend time with a particular tree over time—like at home it’s the tree that’s right outside my window that I see everyday—writing about it, reading to it, letting it edit my work, asking it questions. This is a practice I learned from Camilla Nelson in a workshop where we spent several days ‘collaborating’ with a tree. One of the most profound experiences of editing and also of empathy I’ve ever had was reading what I had written back to the tree. The feedback was immediate. It was no different than reading something to a person you respect, about them—they don’t even have to say anything, just their presence tells you where you’re off, or bullshitting. In the workshop, I should say that we first read what we had written with the tree inside, to each other, the other human writers, and it all seemed pretty great. Then we went outside and read the same piece to the tree. And the tree was like nahhhhh. It was SO different, and so clear what had to go or change. So I think that has a lot to do with basic empathy, not just imagining into another person’s experience, but also checking your version of that with them, which at first might seem tricky when they don’t have a mouth or can’t speak, but really their presence speaks incredibly clearly.

I grew up on an island in BC, three ferries from the mainland. The island is covered in temperate rainforest and bluffs and has nine lakes, and I just wanted to stay inside and read V.C. Andrews novels and one day move to a city. Nature to me wasn’t so interesting. When I was 19 I moved to Montréal, and it was there that a felt sense of ecological presence was like—hello… One experience in particular—I was on the third floor of a walk-up in the Plateau and could suddenly feel the earth coming up through the floor. I don’t know how else to describe it—just this presence or force, very clearly, from out of nowhere. And I remember being fascinated by how the vines and trees grew out of the tiniest spaces of dirt in the pavement. I guess it’s how a city kid might feel moving to the country, but reversed. Like, where’s the 7-Eleven? It wasn’t that I was homesick (though I was), it was this amazing felt sense of ‘nature’ suddenly palpable to me, emanating and pulsing up through my building, pushing out of the pavement exuberantly. So then I became very interested in writing about it but I found my concepts about ‘nature’ pretty limited. And also that it felt awkward to write ‘about’ nature—which in itself set ‘it’ apart—a category mistake that makes it difficult to address questions about our relationship to nature.

KdP: A memorable poem for me repurposes tree names into parts of speech, yew becomes the pronoun you, pine becomes the verb, fir warps into for. In this poem, you are able to transform grammar and syntax into a photosynthetic system, which cleanses the pollution and corruption and heartache of contemporary living. Do you consider this kind of transubstantiating writing practice as hopeful? If everything is a forest, so to speak, what are the implications for growth in an age that the environment has not been put first?

Transformations in language feel urgent to me, yes, maybe because my ideas about what I know are so limited, and it’s a way of exploring and pushing those limits, turning them into something else. I think I’ve always felt that if I could find the right words I could make something happen, or stop happening—which as my friend Joni pointed out is really the idea of the spell, writing as spell-ing. I mean this in a really practical way, as impractical as poetry might be. If the entire late capitalist worldview is built upon thinking of nature as resources, essentially unfeeling, unthinking and inert, to interrogate this idea, to see it as an idea, and to have a different idea—is to have a different experience of the world. One that converses with you. That to me is radically hopeful.

KdP: Just briefly, tell me more about the oysters you used to eat as a child! The relativity of five star treats…

Haha well oysters are really everywhere where I grew up. They’re farmed and shipped all over the place, and they also grow happily on the beaches, often to an enormous size. So we ate them a lot in my family, my mum liked to fry them. We’d go out and shuck them off the rocks and eat them for supper, I think she was pretty pleased about being able to forage such treats. But I in my kid way found them disgusting—unlike a fish, which you gut, you just eat an oyster’s entire body, including its guts… so I would often consider that while I was eating. (Which was actually a reasonable concern, since we lived across the water from a pulp mill spewing dioxins into the ocean, and the oysters were old bottom feeders—not the kind you get in an oyster bar. As I later learned.) Anyway, when I first moved out of home I lived in a tent on the beach with my friend Elise, and often we wouldn’t have any food, so then I’d reluctantly go shuck oysters and fry them for breakfast. Then I sort of appreciated them more—they were elevated to the level of ‘free protein.’

KdP: Are there any ecological writers, poets, thinkers who you’ve been inspired by and would recommend to other readers? And what is the importance of (non-scientific, non-pedagogical), but ecologically-aware literature?

Crucially! Luxuriously. So many people in so many ways. Poetry-wise, Lisa Robertson, angela rawlings, Aisha Sasha John, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, Inger Christensen, Julie Joosten, Liz Howard, Juliana Spahr, Cecilia Vicuña, CA Conrad, Emily Dickinson, Ariana Reines, Jacob Wren all unlocked some massive piece for me.

Also Donna Haraway, Bruno Latour, Amitav Ghosh, Anna Tsing, Timothy Morton, Deleuze & Guattari, Camilla Nelson, Rupert Sheldrake, David Abram, Michael Stone, Robert Nichols, Hélène Cixous have all been important to my thinking. Among so many others—including everyone I want and need to read.

I talk about what I think ecologically-aware literature can do throughout, so I’ll let that speak to your question, but I will also just hit it over the head and say that since the ecological crisis underpins really everything unless we’re moving to Mars, it’s worth trying to find new ways to think about the situation, and literature and art are probably some of the best ways to do that. Wittgenstein’s “The limits of my language means the limits of my world” thought is so terrifyingly clear to see right now—and gives me hope by the same token.

KdP: I’ve been fortunate to attend your performances This ritual is not an accident and Facing away from that which is coming. I’m curious whether your work as a choreography and dancer, which is often collaborative in nature, influences your writing practice? Is your writing solitary in comparison to your work as a performer? How do you feel you influence and connect (or don’t) with peers and the larger literary community?

I love that you saw both of those! It means a lot to talk with someone who’s seen the full spectrum of what I’m trying to make. First, yes—dance and performance influence my writing very much. I’ve always felt them as very connected, at first by their seeming absolute otherness—as if far apart enough on the discipline spectrum that they are actually right next to each other. The intelligence of the body and of the mind, and how those things aren’t actually separate, and the ways that they crossfire (I write much better if I dance—I think because dance requires such a different kind of rigorous mental work). For me they’re both about finding new ways to inhabit and extend and transform thought.

In terms of how dance influences my writing practice—there are some concrete ways, like thinking about the space of a page as space in which language can move. The alive space of a page feels similar to a studio. angela rawlings was/is a huge influence and inspiration for that. I also use physical/sensorial practices in my writing practice, such as the ones I discuss earlier. I also love to write while watching dance, which I often do at rehearsals and performances—because I’m interested in the way movement triggers or translates into language.

I suppose that writing is quite solitary compared to collaborative performance making, but because I do both, the solitude and nimbleness of it usually feels welcome. And performance making pulls me out of my tendency to homebound introversion, so it’s a good balance ☺

In terms of peers and literary community, for a long time I didn’t really feel I belonged anywhere. But don’t most artists sort of feel like that, at least at some point? For me it was an important part of the process and also of finding my communities.

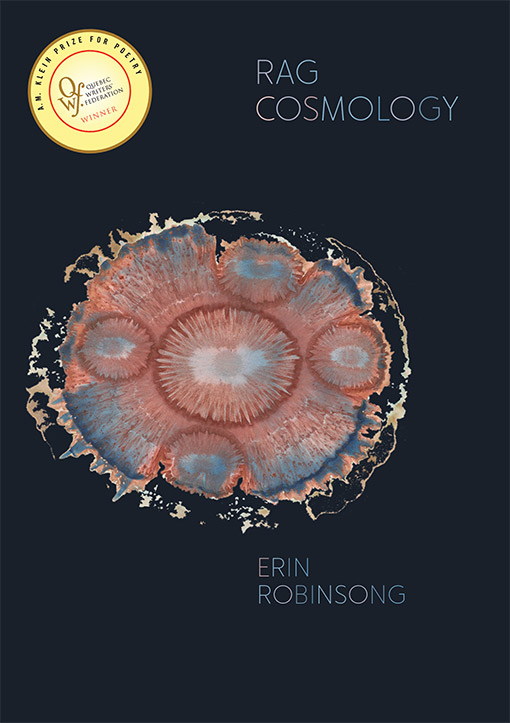

KdP: November 2017, Rag Cosmology won the prestigious Quebec Writers’ Federation A. M. Klein Prize for Poetry. What has this meant for you professionally? How do you feel about this personally?

Well personally it was deeply gratifying and surreal to have my book be so seen by the judges, seen to be doing the thing I’d only ever been trying to do. Before that, I wasn’t sure that I had at all achieved what I’d set out to do (and ‘achieve’ is the wrong word), but hearing their citations, I had the uncanny sense of my book reading as I had most wished. So that was amazing.

Professionally it’s expanded the book’s reach, which is the best thing that can happen to a book. And as a longtime ‘emerging writer’ (I’ve been slow to publish) it’s helped me emerge with a bang! I don’t quite know what this means yet, but I’m so grateful for all the things and people that came together for this to happen.

KdP: Finally, your poetic landscapes seem to follow me. (I am currently in Cape Town, South Africa, where a major drought is waging, fresh water may be completely depleted here in a matter of weeks. And yet, the city is surrounded by water in the form of ocean. Swimming, I imagine jumping through the choppy waves of your poem:)

Sorry that was a tangent. I meant to ask whether the landscape of your immediate surroundings impact your writing? Whether you write about oceans while at the sea, cities while cityliving? Or do you have a reserve bank of topographical inspiration from past experience? Guess I could rephrase that: what is the autobiographical accuracy and importance of landscape in your writing?

God—I’ve been thinking about Cape Town so much these days, living what we’ve been talking about in regards to water for so long. It was amazing to hear you talk a bit about this the other night, the water rationing, the water desalination race, the leaving town for other less but also dry areas… I am apprehensive and also deeply curious to see what people living there will come up with to deal with the fact of their entire city running out of water. So thank you for that deeply relevant ‘tangent.’

In terms of your question, when I’m writing I definitely relate with what’s around me- but this is less landscape and more particular trees, encounters, and ideas which I think are always in relationship to landscape, though maybe not in an obvious sense. So in this book—(I’m looking through to see what was written where) I wrote about coral reefs while in the mountains (watching a lot of youtube clips, in mountains made of ancient seabeads), I wrote about marriage while unmarried, I wrote about the Pacific garbage patch while in Toronto and climate chaos in mild weather in London. So I want to say yes, my surroundings impact my writing in the extreme, but not in a mirrored way. It’s more sensitive, like an ecosystem—it’s the light, it’s something someone said, it’s the book I’m reading, it’s something on the news, it’s weather, it’s what I’m sitting on, what I ate, it’s something I wrote in a notebook ages ago that suddenly means something to me—and probably the way the landscape I grew up in continues to influence me in such fundamental ways I could never untangle from who I am and how I perceive.

Erin Robinsong is a poet and interdisciplinary artist thinking about ecology, interventions, and pleasure in her work. Her writing has been published in places such as Regreen: New Canadian Ecological Poetry; Dandelion; The Capilano Review; The Goose; among others, and is forthcoming in Counter-Desecration: A Glossary for Writing Within The Anthropocene. Her debut collection of poetry, Rag Cosmology, published with BookThug in 2017, won the QWF’s A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry. Recent performance work with choreographer Andréa de Keijzer includes Facing away from that which is coming and This ritual is not an accident. Originally from Cortes Island, Erin lives in Montréal.